[This is part of BFNow Self-Study Module 2: Objects, Categories, Territories & Maps. For more about the overall Self-Study program, please look at About BFNow Self-Study and BFNow Self-Study Orientation.]

If you haven’t done so already, let me encourage you to pause, relax and release your cheeks and your jaw and take three deep breaths.

We move from objects to categories (just as infants do) …

Categories

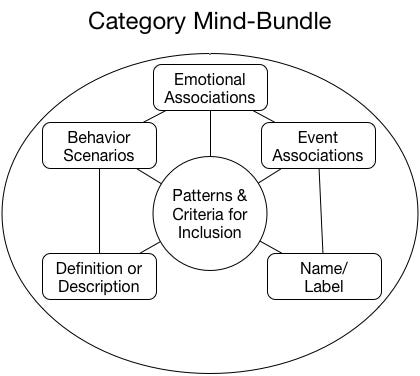

Cognitive psychologists make a distinction between the term category (as a set containing instances or members) and the term concept (as the description and criteria for that set). I’m going to treat these as two sides of the same coin since every category has an associated concept and every concept implies a category. From my perspective, they are just different aspects of the same mind-bundle that I will refer to as a category.

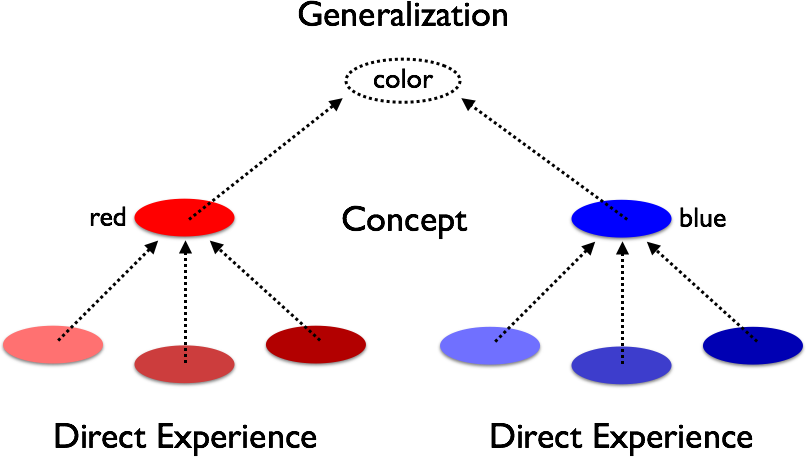

Categories are a generalization and abstraction from objects (their characteristics and behavior) and events (as time objects), as in this slide from hOS Literacy Part 4, starting at 3:38 and going to 4:54:

Each direct experience provides an instance of red or blue. Red and blue are instances of color. Categories can be bundled into still more generalized categories, up as many levels as you choose to go, but these hierarchies of abstraction all rest, eventually, on direct experience.

The process of abstraction and generalization throws away everything that is unique about each instance. In that process, categories become even more distant from contexts and relationships that were part of the direct experience. Consciously or not, we tend to create context-independent definitions for categories, so the category can be used in any situation, anywhere, at any time. In common usage, we generally behave as if our categories are universal and absolute.

Just like object perception is the original augmented-reality technology, so too category-based thinking is the original virtual-reality technology. It is also so convincing that we fail to recognize that, as a representation of what’s “out there,” it’s crude and error prone.

The mind-bundle for a category is a lot like the mind-bundle for an object:

Like objects, categories depend on the what pathway and developed for the same evolutionary reasons. Indeed, the ability to group objects into categories and then learn behavior scenarios for the category is even more useful than just learning behavior scenarios for an individual object. If you find a plant that turns out to be good to eat, you want to be able to transfer that experience to other plants of the same type.

When humans developed language, language then created the opportunity to associate categories at various levels of abstraction with specific sounds (words) – a kind of auditory object. Visual symbols (including writing) can likewise be the anchor-point for abstract mind-bundles. So, in humans, the what pathway gets extended and repurposed to support all kinds of abstract categories.

Category mind-bundles share all of the strengths that go with object mind-bundles:

Assignment to a category is usually a quick, thinking-fast, largely subconscious process.

Category mind-bundles can contain – and serve up to our awareness – a huge amount of associated information.

Yet categories also share the limitations of object mind-bundles. For example:

The what pathway deals with categories as units. The associated description, behavior scenarios, etc. are attached to the category as a whole. This can be an inflexible one-size-fits-all approach and is the basis for stereotyping.

The heavy dependence on thinking-fast makes categorical snap judgements simplistic and error prone.

Categorical Thinking

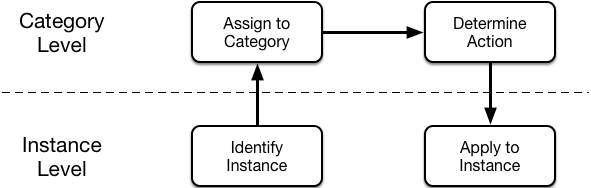

The basic pattern for categorical thinking looks like this:

For example, you see a red roundish object on a tree (instance), decide that it is an apple (category), decide to eat it (action based on what you know about the category) and bite into that red roundish object (application of action to the instance).

Notice that the choice of what action to take is based purely on the qualities of the category. Whatever individuality the instance might have isn’t considered. This is what I mean by categorical thinking.

Most of the time this is a quick, efficient, and largely subconscious process with good results. We could hardly live without this kind of categorical thinking.

But this kind of categorical thinking doesn’t always work well. Here are some examples. You may think of others.

The individuality of the instance matters – Suppose that before you bite into the apple you notice that it has worm holes or is moldy or has a residue that could be pesticide. Perhaps you shouldn’t eat it after all.

The context of the instance matters – Suppose the tree is in an agricultural research orchard where only the researchers are allowed to pick the fruit.

Relationships matter – Suppose the apple you first saw is by itself on a strong branch but close to it is a cluster of apples on another branch that are weighing down the branch almost to the breaking point. Wouldn’t it be better to take your apple from the cluster?

The variation in instances is too continuous to easily categorize – We saw this with colors in hOS Literacy Part 3, starting at 15:47. If you are doing serious work with colors, naming them is too inexact. In this case the reliance on the what pathway breaks down and we need to turn to the spatially-oriented where pathway and visual or numeric representations.

The wrong category is given priority – Most objects could be assigned to many different categories (or combinations of categories). Which category gets priority can make a big difference in the action you choose. Typical is the story of a UC Berkeley student who was supposed to fly from LA back to Oakland but he got bumped from the plane for speaking Arabic. It turns out that Khairuldeen Makhzoomi could be put in many categories: Iraqi refugee, invitee to a dinner with Secretary-General of the United Nations Ban Ki-moon, son of an Iraqi diplomat killed under Saddam Hussein’s regime, person in phone contact with someone (his uncle) in Iraq, senior at UC Berkeley, frequent flyer on the airline that bumped him, and someone who ends his conversation saying “inshallah” (if God is willing). The last category was what got him bumped. This is just one small example of the millions of bad choices that flow out of stereotyping and bad categorizing.

Polarity “logic” run amok – There are many polarity pairs: good-bad, true-false, accurate-inaccurate, etc.. These are supposed to be clear-cut, black and white divisions yet much of real life doesn’t fit such a rigid and simplistic scheme. As I said in hOS Literacy Part 4, starting at 8:30, I usually prefer replacing these categorical polarities with the metaphor of signal and noise. When people think categorically, the critic finds some noise and declares that there can’t be any signal because of the noise. while the proponent, enthralled with the signal, denies there can be any noise.

It’s got to be one or the other – Even if the alternate categories aren’t polarities, we often feel that we need to choose one of them. Are these particular Syrian rebels “terrorists” or “freedom fighters”? Is what I’m experiencing in my life now the result of my actions or not? Which of the two parties in a civil lawsuit is at fault?

So is categorical thinking bad? That would be too categorical! Rather, categorical thinking works well in some situations and not so well in others. The real problem, as I see it, is the monopoly that categorical thinking has over our minds. Our cultures default to categorical thinking without much sense of where it does and doesn’t work – and with little sense of what other kind of thinking could be used instead. We’ll start into those alternatives in the next exploration post, building on this understanding of the strengths and limits to categorical thinking.

Experientials

1) In appreciation of categorical thinking

Make this brief. Think of a few places in your life where categorical thinking works well for you. Perhaps you use a recipe for cooking rice without needing to newly learn how to cook each individual grain of rice. Or you have settled on what brand of eggs to buy and don’t need to compare all of the eggs in all of the cartons each time. While these may seem like trivial take-for-granted examples, imagine if you couldn’t do this kind of everyday categorical thinking! There are likely thousands of places throughout your daily life where it is just so much more efficient to think categorically. Any of those will work fine for this experiential, in some ways the more seemingly trivial the better. Write down a few in your journal and appreciate what’s good about categorical thinking.

2) Where categorical thinking doesn’t work

Start this in your morning if you can and carry it into your day. You’ll be building a list of examples. Look back over your life for specific situations where categorical thinking didn’t work well for you. Maybe other people treated you via a stereotype (as an instance of a category) rather than the unique person you are. Or maybe you did that to someone else to your later chagrin. Read over the bullet list above for inspiration if needed and/or come up with different categorical dysfunctions. In any case, explore into what didn’t work and why.

If you aren’t coming up with enough examples in your own life, look to the culture around you. Take any big abstract concept, like freedom, and consider what happens when that concept is treated as an object-like unit with a single definition. Then tie this back to your own life.

However you do it, the goal is to reconnect with your experience of the limits and pitfalls of categorical thinking.

List as many personally-relevant examples as you come up with in your journal throughout your day. Review your list in the evening, adding to it if that feels right. We will return to and build on this list in explorations 4 and 5.

If you have questions or comments, please post them here.

Thanks,

Robert

[Link back to the Module 2: Objects, Categories, Territories & Maps Overview page.]