[This is part of BFNow Self-Study Module 6: How Change Works. For more about the overall Self-Study program, please look at About BFNow Self-Study and BFNow Self-Study Orientation.]

If you haven’t done so already, let me encourage you to pause, relax and release, perhaps with a big stretch or three deep breaths.

This module’s goal is to get a deeper understanding of how change works in human systems, especially in groups and cultures. We’ll be doing this with the help of insights from a variety of perspectives.

We start today with exploring what are technically known as Complex Adaptive Systems (CASs) although I also like to think of them as Living Systems. The goal of this exploration is to create a common ground of language and concepts that we can build on as the module progresses.

Discovering the territory

So far we’ve been dealing with systems that are relatively simple, like the habits diagram. CASs are different. Even though they are both called “systems,” I encourage you to look at Complex Adaptive Systems as a whole new territory – a territory of systems that are complex in their many elements and interactions, and adaptive in their ability to respond to external and internal changes.

Perhaps the easiest way to start to understand them is through examples. Each of the following can be usefully modeled as a CAS: cities, markets, supply chains, ecosystems, social networks, the immune system, power grids, animal swarms, the human brain, developing embryos, ant colonies, the human psyche and, of particular interest for us, human groups and cultures.

What the above examples all have in common are agents, emergence and evolution.

Agents (or players or actors)

The fundamental element/part/node in a CAS has agency – the ability to affect the element’s situation/environment through intentional or at least context-responsive action. The academics like to call these elements “agents” but I often prefer “players” and “actors” and will use the terms interchangeably.

Examples of CASs with their agents/players/actors include:

Ourselves, where the players are our subpersonalities

Ecosystems, where the actors are the various species and their individual members

Cities, where the agents are both the residents and the city’s businesses and organizations

The immune system, where the actors are various kinds of cells

Markets, where the players are sellers and buyers plus any market-enabling institutions (from farmers’s market to the stock market)

Ant colonies, where the agents are the ants

In a typical CAS, there are a large number of similar-but-not-identical agents – too many to track in detail

There can be more than one type of agent in a CAS – different subgroups or even different categories, e.g. a city has residents and businesses as different categories of agents

Agents are semi-autonomous; each has a mind of its own, makes its own choices and can produce unpredictable outcomes

At the same time, agents are interdependent – with each other, with various categories of agents and with the context.

Each agent is influenced by many others, by the broader context, by its own capacities and by its own history

In the context of all of this influence, each agent is able to adapt, that is, to learn new behaviors; that’s what makes it an adaptive system

A CAS can have more parts than just its agents/players/actors. For example, a city has it buildings and physical infrastructure. It also has a government and related social infrastructure.

Emergence

While the individual agents can be fascinating, you can’t get the full picture of CASs without also taking into account the relationships and interactions. A CAS is very much a case where the whole is more than the sum of the parts. The diversity, entanglement and often hidden character of interactions is what makes a CAS complex.

Think of how complex a human group is with all the interactions that happen inside each person, among the people in the group and for each person with the context outside the group. It is impossible to track all of those interactions, yet they have major consequences.

Out of this complexity, there often emerge patterns in the system as a whole that can’t be predicted from studying the individual agents in isolation. This phenomenon is known as emergence, which is really just a fancy term for the ability of a CAS to generate patterns that depend on interactions and relationships.

The results of emergence in natural systems can often be quite beautiful. Consider this example of what’s called murmuration in starlings, as illustrated by this half-minute video.

It turns out you can model this behavior accurately by assuming each bird follows a simple set of rules:

Stay close but not too close to a half-dozen or so others around you

Align your speed and direction with the same half-dozen or so others

Notice that there is no leader bird that all the others are following. Rather they are involved in a process of self-organizing with no command and control hierarchy – yet the system has order. Self-organization is often cited as a classic emergent pattern.

Once you start looking, you see emergent patterns everywhere. For example, all of the shared aspects of culture – ideas, behaviors and artifacts – are examples of emergent patterns. Language, specifically, is great example of an emergent property of culture that resides in individuals yet only exists because people are in relationship with each other. Much of what we think of as defining characteristics of “being human” are in fact shared emergent patterns of culture.

Emergent patterns grow out of co-evolution, a process of mutual adaptation (learning) as each agent discovers, co-creates and internalizes the rules and roles that enable the pattern to work. Once you have the shared pattern, it can seem to emerge spontaneously and instantly but the ability to create the pattern was likely a long time in the making.

Evolution

The third major characteristic of CASs is their ability to change. I’ve alluded to this a number of times above and I’ll go into this more tomorrow by looking at the evolution of culture. Nevertheless, it is important to call it out here.

Change in CASs is usually referred to as evolution because it occurs through many small steps as agents keep adjusting to the changes happening around them. Each round of changes then prompts a new round until some new pattern of stability is reached.

This is wonderfully illustrated in How Wolves Change Rivers. With over 43 million views, it’s well worth watching. I recommend it.

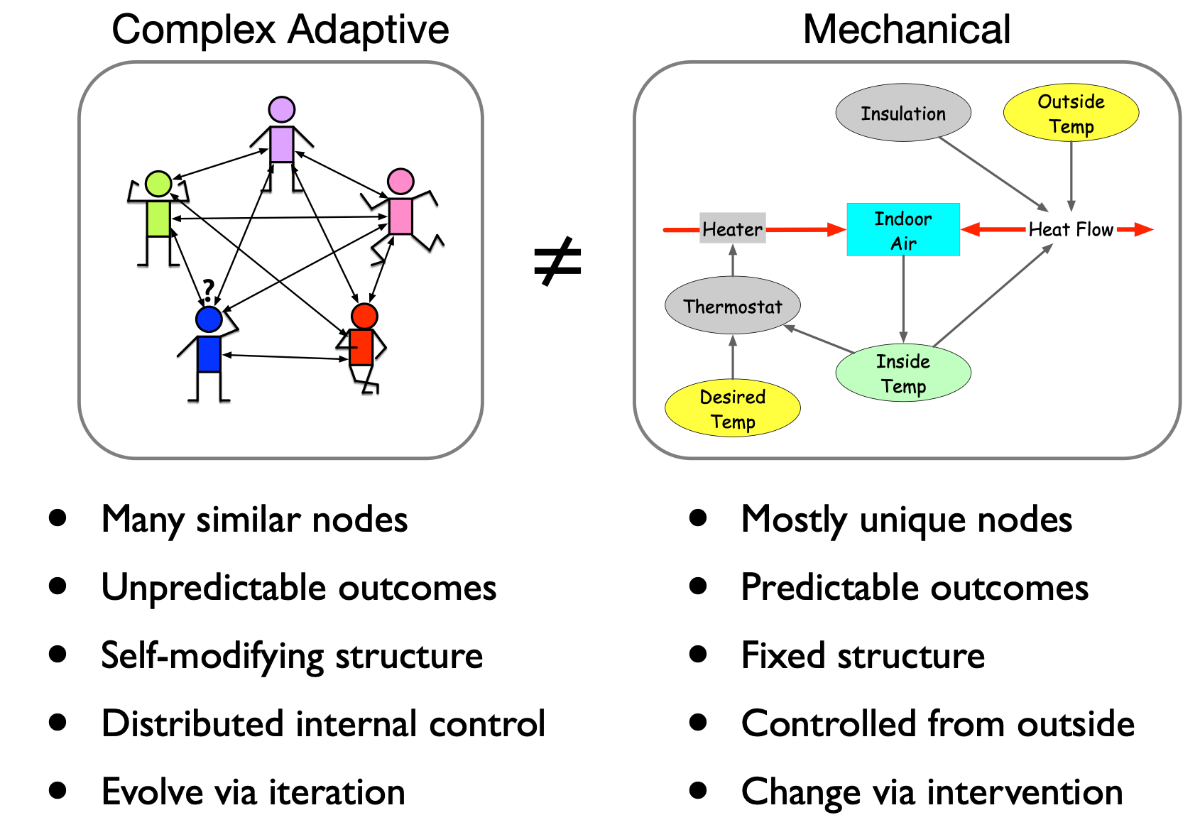

Contrast with mechanical systems

Finally, I’d like to share one of the slides out of the Stoa presentation to draw a contrast between CASs and mechanical systems, like the Home Heating example in Systems Literacy – Part 3. Our culture is so used to attempting to see systems in mechanistic terms that it’s important to reinforce the ways in which CASs are not machines.

Mechanical systems can be modeled in detail, and designed and built to specifications. CASs not so much (although there is some computer modeling of simplified CASs). Rather, the CAS framework provides a language for harvesting observations of how natural CASs work and being able to compare and contrast across different systems – as I did in What Time Is It? by applying lessons from pioneer and succession species in ecosystems to human population growth and culture.

Experiential

Identify a few different territories that you feel can be usefully understood as complex adaptive systems. They could be human groupings or something else. Identify the various different types of agents in each system. In addition, what do you see as emergent properties in each, that is, what are properties or characteristics in the system that require relationships among agents to emerge?

Look for places where our culture tries to force a mechanical model onto territories that could be better understood as CASs. Bureaucratic organizations are one example. Many aspects of government are another. Pick a specific group or organization, not just a category, that you’re familiar with and see how your understanding shifts if you look at it as a Complex Adaptive System.

As always, use your journal to capture whatever feels useful.

If you have questions or comments, please post them here.

Thanks,

Robert

[Link back to the Module 6: How Change Works Overview page.]