[This is part of BFNow Self-Study Module 6: How Change Works. For more about the overall Self-Study program, please look at About BFNow Self-Study and BFNow Self-Study Orientation.]

If you haven’t done so already, let me encourage you to pause, relax and release, perhaps with a big stretch or three deep breaths.

The goal of this exploration is to provide you with some frameworks and tools to support your conscious participation in cultural evolution. As you explore this territory, please consider …

In its 13+ billion years, the universe has gone through many different types of evolution. First there was the evolution of physical structure, going from just hydrogen and helium gas to clumps that formed stars and galaxies. That led to chemical evolution as all of the elements heavier than hydrogen were formed in the cores of stars and spread back into space through end-of-life stellar explosions. Those heavier elements allowed the formation of planets around later generations of stars, like our Sun. All of these forms of evolution moved slowly, over billions of years.

Once there were planets, the evolution of life became possible. On the earth, that’s moved a bit faster but still with a pace best measured in millions or hundreds of thousands of years.

Cultural evolution has only been around on the earth for a few hundred-thousand years and it was very slow until about 12,000 years ago. Even in that more recent span, it has been slow enough so that most of our recent ancestors wouldn’t have noticed much foundational change in a lifetime.

But the pace has sped up, first in the last few hundred years and now even more rapidly in the last few decades. Those of us alive today are among the first generations to experience deep cultural evolution over the span of a lifetime or less. We may be the first to be able to consciously engage in shaping this evolution – to be conscious co-evolvers.

Take a moment to really absorb this …

The first generations with the opportunity to meaningfully experience the cultural evolution we consciously help to create.

This exploration is a small step in that direction.

Culture as a Complex Adaptive System

In the simplest definitional terms, I use culture to mean the combination of

the patterns of behaviors, ideas and artifacts shared by an interacting group of people

that interacting group of people

In CAS terms,

the people are the players

the behaviors, ideas and artifacts are the emergent properties

the culture that includes the players and emergent properties is the complex adaptive system.

When we talk about “cultural evolution,” we’re talking about evolution in those emergent properties: in the shared behaviors, ideas and artifacts.

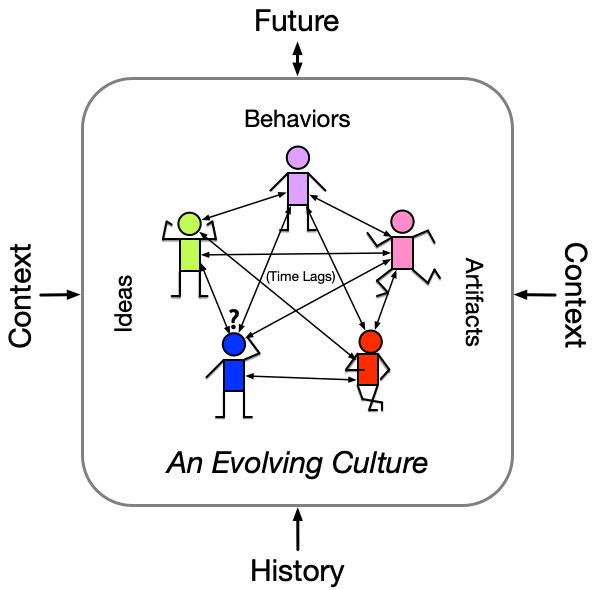

There are many factors that influence how that evolution proceeds. I like to represent them schematically like this …

Players or Agents – At the heart of the diagram are the people of the culture – making choices, interacting, initiating and reacting. I’ve used images for individuals but organizations can also be players. I’ve shown only five but there can be millions in a culture, each one a potential source of initiative and influence. Some players will have more influence than others but everyone has some and no one has it all. All of these multiple sources of initiative make it impossible to predict, in a mechanical way, what the system will do.

Ideas, Behaviors, Artifacts – These are the emergent properties the people share – the water they swim in. They are also what change as a culture evolves. I’m using these words quite generally. In this setting, take them as shorthand for all the various dimensions of culture, including such things as beliefs, language, customs, institutions, buildings and technologies.

The Interactions – The players are constantly being influenced by and reacting to each other. Sometimes they learn from each other; sometimes they push back in opposition to each other. Sometimes they just observe each other; sometimes they are oblivious to at least some of the others. Sometimes the influence is direct; sometimes it’s indirect. Sometimes it’s fast; sometimes it takes a long time.

Time Lags – These are all over the place in culture! When someone makes a change (in their ideas, behaviors and/or artifacts), it takes time for others to even become aware of that change, much less respond (pro or con) to it. Depending on the change and who’s involved, these time lags can range from seconds to decades, yet taken as a whole they provide significant inertia to culture and constrain the pace of change.

Tipping Points – These aren’t in the diagram but they are also all over the place in culture. They often show up in shifts of the “majority opinion” or “conventional wisdom.” These shifts may make it seem like rapid change has happened although if you look closely there has usually been a long build-up to the actual tipping point.

The Boundary – Cultures have boundaries. The edges may be blurry but it’s generally clear enough as to who and what are part of a culture. This boundary allows the culture to have unique qualities and to change in ways that may be different from what’s around it. Cultures also nest, that is, subcultures exist inside larger cultures or even other subcultures. It can get quite complex!

Context – Every culture is surrounded by a wider world – including other cultures and natural systems – that provide it context. Just what gets considered as “context” versus what’s part of the culture will be unique to each culture. “Context” is meant to be external to the culture, including all of those systems and elements over which the culture has relatively little influence. I’ve used one-way arrows for the influence of the context on the culture to reflect this relationship.

The Sun and the seasons are clearly part of the context. Climate used to be but now it’s starting to straddle the internal/external boundary with all of the human influence on climate. Among national cultures, each is in the context of the others although together you can think of each nation as an important player in the culture we call humanity. More generally, subcultures of the same larger culture are in the context of both each other and of that larger culture.

History – Culture is built on accumulated learning and so is tightly connected to the past. Each moment grows out of what has come before, often reaching back hundreds or even thousands of years. This, combined with time lags, makes for a lot of inertia in culture.

Future – Obviously, the evolution of a culture affects its future but why have the arrow of influence point both ways? One reason is that beliefs about the future play an important role in shaping the choices the players make in the present. Are the players optimistic or pessimistic? What do they expect their world to be like in 10 years, 30 years or more?

Another reason is that there is a fair bit of evidence that people can – with a lot of noise but still some signal – intuit potentials in the future. It’s hard to know to what extent this “whisper of the future” may influence people but I don’t discount it. I see this through the lens of the futurist idea of “the range of possible futures.” I don’t feel the future is set but rather there are a range of possibilities and our choices determine which ones manifest.

OK, so these are all aspects of the system, but how do they all come together in the process of cultural evolution? In practice, this is a very complex system and to gain some insight into how it functions, it’s helpful to look at real examples.

Learnings from cultural and biological history

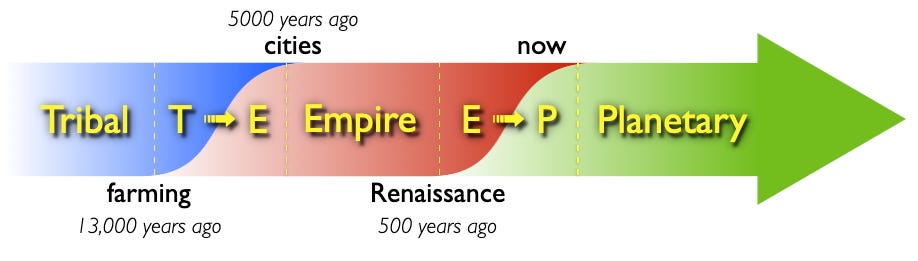

Let’s start with cultural history. In What Time Is It?, I focused on three foundational cultural characteristics:

Means of livelihood

Advanced form of communication

Basis of social organization

Tracing these through the past 40,000+ years of cultural history leads to what I like to call the Outline of History:

This outline has an alternation of stable periods and transitions. This may seem surprising – why isn’t it just one continuous stream of change? – but it parallels what is now understood as the common pattern in biological evolution.

Up until the early 1970s, evolutionary biologists generally assumed that changes in the traits of species happened continuously, although slowly, and led to an ever-better fit between the species and its environment. When two lineages of the same ancestor were separated geographically, this slow, steady drift of traits could eventually create different species. This is known as Gradualism.

Examples of this kind of gradual drift of a species’ traits do occur in the fossil record but they are not the most common examples. In the early 1970s, paleontologists Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould championed the evidence that the more common pattern is what they called Punctuated Equilibrium.

In this pattern, a species’ traits are stable (known as stasis) over long periods of geological time after going through an abrupt transition that left no trace of intermediate forms in the fossil record. That doesn’t mean the transition was instantaneous. Given the slow and irregular pace of the geological record, the transition could have lasted as much as 100,000 years while the stasis periods stretched over millions of years.

What’s going on here?

Species evolve most rapidly after a major change of context, such as a mass extinction. Post-extinction, there are many unoccupied niches that create a lot of opportunities for the organisms that did survive. In this initial period, the internal rate of mutation within the species is the limiting factor on the pace of evolution. The context is wide open and allows for rapid species drift.

Later, as the niches become filled and the new set of species establish their web of interdependence, the “cup” of stability that each species finds itself in becomes deeper. Species continue to experience variations but those variations rarely lead to improvements over their established sweet-spot – so the result is stasis.

Should we tear down “the old ways” first?

You could look at the example of biological evolution and say that we need to create “an extinction event” in order to enable change but that’s not how I look at it. This is a place where we need to be careful in how we interpret the parallel between biological evolution and cultural evolution.

In both of the big cultural transitions, the driving force was the cultural expansion into previously unrecognized opportunities:

In the Tribal to Empire transition, the opportunity was opened up by farming, storable food and settlement. As cultures explored into this new space, more innovations led to yet more until the stability of the Empire Era was reached. There’s no solid evidence that this was initiated in response to adversity.

In our current Empire to Planetary transition, the opportunity was opened up by the natural sciences and their practical applications. It’s possible that the Black Death helped to loosen old cultural patterns but it wasn’t until Europe was becoming prosperous that the cycle of innovation took off.

The ability to discover and then evolve into previously unrecognized opportunities seems to be a uniquely human trait enabled by culture.

This doesn’t mean that there won’t be destruction and breakdown in the current transition – clearly there’s already a lot and there will likely be more. The question is, where should we put our attention and effort?

I find it helpful to explore this with the help of …

The Equation of Change

This says that people will adopt a new way when [the perceived value of the new] is enough greater than [the perceived value of the old] so that their difference is greater than [the perceived cost of the change].

One of the useful system concepts here is the idea of the current constraint. From the perspective of assisting cultural change, what’s the limiting factor? It will all depend on the specifics but I would suggest that there are currently a large number of situations where people already feel that the old way doesn’t work. It’s fine to have a cogent critique of the old but you don’t need to belabor it. What’s holding them back is a lack of vision and even more so a lack of practical, tested pathways to get there.

Because those pathways are the current constraint, we have the most leverage by focusing on creating and implementing them and thereby both raising the perceived value of the new and lowering the perceived cost of the change.

Back cover image from In Context #9 – Strategies for Cultural Change, Spring 1985

Experiential

Think of a situation where you would like to see meaningful cultural change. It could be on any scale – from a small group you are part of to something worldwide.

Read over the list of aspects under the diagram in the Culture as a Complex Adaptive System section. See if any of them prompt insights into a better understanding of the situation and/or places to intervene to promote change. For example, could the pattern of interactions be changed, time lags reduced or the relationship with the context shifted?

Look at that same situation using the Equation of Change. What might you do, in your situation, to shift [the perceived value of the new] up and [the perceived value of the old] and [the perceived cost of the change] down?

If you have questions or comments, please post them here.

Thanks,

Robert

[Link back to the Module 6: How Change Works Overview page.]