Dealing with Dominator Behavior - Part 1

First steps towards a fresh approach to this profound human problem

I’ll be exploring this theme in a series of posts that have two main purposes:

First, to initiate meaningful progress on making dominator behavior obsolete by developing fresh understandings and approaches for resolving this persistent human challenge.

Second, to illustrate how the Foundational Keys can be used to help develop these fresh understandings and approaches.

If we can accomplish these goals, the benefits and implications will be huge. Solving the puzzle of dealing with dominator behavior is the last big step in the multi-century transition from the Empire Era (where the basis of social organization was violence-enforced, religiously- or ideologically-sanctioned dominator hierarchy) to the Planetary Era (where the expectation is that the basis of social organization will be win-win-win consensual collaboration).

What is dominator behavior?

I’ll start by describing dominator behavior as a way of relating that attempts to establish or maintain a power hierarchy and treats the "other" as an exploitable resource. The "other" can be another person, group or some part of nature. It can even be an internal part of a dominator, as in the domination of mind over body or will over feelings.

Dominators pursue the goal of ‘Enforce the three dominations: over self, over others and over nature.’ This stands in stark contrast to the goal in the Foundational Keys of ‘Embody the three harmonies: within, with others and with nature.’

It’s also about more than the behavior of obvious bullies or the people at the top of dominator hierarchies. Except for those at the bottom, everyone at any level in those hierarchies participates to some degree. That includes a lot of us.

You've no doubt seen and felt dominator behavior many times. I know from experience how personally and persistently damaging it can be – and I've had it relatively easy. I grieve for the vast majority of humanity who live constantly with dominator behavior and its consequences. This motivates me every day in my work to accelerate the transition to the Planetary Era and has for over 45 years.

Dominator behavior has always been part of the range of possible human behaviors. Nomadic hunting and gathering cultures had effective ways to keep it in check (see here, here and more deeply here). Agricultural cultures mostly succumbed to dominator behavior as an acceptable pattern. Over the past five thousand years it entrenched itself as the basis for social organization in agrarian empires around the world.

We're obviously still dealing with that heritage today, and not just at a large-scale political and international level. Dominator behavior happens at all levels throughout daily life. Think back to the last time you watched someone talk over another in a meeting, dismiss a colleague’s idea, or subtly manipulate a conversation. Maybe you’ve felt the weight of unspoken dominance in a relationship or a system where the rules seem designed to keep power in place. These are persistent patterns, endemic in the culture.

If we are to move to the brighter future of the Planetary Era, we need to remove dominator behavior as the basis for social organization and make it obsolete. The experience of hunting and gathering cultures shows it can be done.

In this series of posts I’ll be exploring how it can be done for our time in history.

Dominator Behavior is Complex

The two words "dominator behavior" can make it sound like a simple thing but it turns out to be a very complex and diverse system.

It takes many forms. It can be violent and openly coercive but it can also be subtle, through psychological manipulation, economic control, information asymmetry, technological superiority, social exclusion and bureaucratic power where rules are selectively enforced. It can be structurally embedded in policies, laws and social norms.

It happens on many different scales: one-to-one, in groups, between groups, via institutions and internationally. It also happens on all these scales from humans to animals and all of nature.

It's about more than stereotyped categories. Groupings like gender, race and class are significant arenas where dominator behavior plays out but there’s more complexity to where and how the behavior shows up than just stereotyping.

The degree of self-awareness covers a wide range. Some people exalt in their role as dominators while others are in denial about what they do. In the many cultures where dominator behavior is the norm, it’s often broadly accepted as simply human nature, what everyone does and the way life works without any awareness that there are other ways of being and behaving.

It involves multiple people. It's a way of relating, so there will always be at least two parties and often more, together creating a relational system in which the behavior plays out. A common pattern for the system is the dominator, the target of the domination and the bystanders. To really understand the behavior, we need to look at each person’s role in the relational system.

Context is important. Each person has multiple contexts that will influence their behavior. What do they see as their interests? Their strengths and weaknesses? What's their trauma history? Who is important in their relationship context? What's their cultural context?

The relative strengths of the parties cover a wide range and can be complex – everything from the strong against the weak to fairly evenly matched. Guerrilla warfare illustrates how traditional ideas about strength don't always correspond to what actually happens.

What's the difference between competition and domination? Many sports can be pursued with a respect for other competitors and an honoring of the rules. Even when there is rivalry, there can still be an understanding that your opponent's skill prompts you to play your best. The key difference lies in whether power differentials are being created and exploited versus whether the competition operates within a framework of mutual respect and agreed-upon boundaries.

Collateral damage is often ignored. Dominators engage in what's described as win-lose behavior but it's actually often win-lose-lose (or worse, lose-lose-lose) where the bystanders and other parts of the wider context also lose. In a no-rules power struggle where the goal is simply relative advantage, the dominators consider it OK to have losses as long as their opponent has bigger losses. In the process, the damage to the wider system isn't considered or seen to matter. War is an obvious example of this process but there are many others.

All in all, dominator behavior is a complex system, deeply embedded throughout the culture, yet making it obsolete is imperative for the survival of humanity and this planet.

We need a fresh approach that enables us to untangle its complexity so we can make real progress in dealing with it.

The Territories & Maps Approach

As the first step in that fresh approach, I’ll be using the territories & maps way of seeing the world as an entry point into how we can begin to think of and respond to dominator behavior differently.

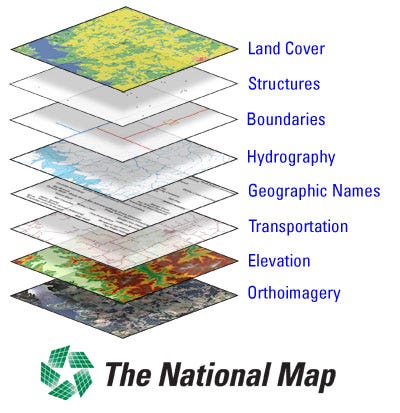

My favorite archetypal example of the territories & maps approach is a Geographic Information System (GIS).

Each layer here is a separate map with its own data and purpose yet they all refer to the same physical territory. Each map contributes to the description of the territory but even all of them together don’t provide a complete description.

This geographic example provides the base metaphor for the more general idea of territory (what is being described) and map (a partial description of the territory).

In its more general use, the territory does not need to be geographic or even physical. Behaviors – like dominator behavior – and ideas – like morality, justice, religion, and freedom – can also be approached as territories, illuminated by multiple maps.

We 'create' territories by choosing where to draw a boundary line to indicate what's in the territory and what isn't. These boundaries aren't meant to be definitive descriptions of the whole territory, they only help us get started so we know where to explore.

The potential for what we could discover in any territory is enormous. Maps gather up what we do discover but a map is not the territory. To be useful, any map can only describe part of what could be known about the territory (it’s partial) and we select what to describe based on our purpose for having the map (it’s selective). Since each map is partial and selective, there is always more that could be learned and ways the map could be modified (thus the map is provisional). This applies not just to geographic maps. Whatever knowledge we have about any kind of territory will always be partial, selective and provisional.

The territories & maps framework is part of the Systems Literacy Key, draws on the HumanOS Key and contributes to the Skillful with Diverse Modes of Cognition Key. It integrates visual and language-based thinking and can incorporate other modes of cognition as well. It gives us a method for working with and understanding vastly greater complexity than our usual categorical thinking. It’s described more fully in BFN Self-Study Module 1 – Objects, Categories, Territories & Maps. It's a first crucial step in using the Keys to unlock new insights into this long-standing challenge.

Dominator Behavior as a Territory

When we treat dominator behavior as a territory, then my statement at the start of this post becomes a description of the boundary of the territory:

Dominator behavior is a way of relating that attempts to establish or maintain a power hierarchy and treats the 'other' as an exploitable resource.

As we get into exploring the territory, we may discover areas where this boundary description doesn't provide enough clarity for what’s in the territory and what’s out. That's fine. The process is meant to be iterative and open-ended. All we need now is a place to start and amendments can follow if needed.

We can also look back and see that the different characteristics for dominator behavior – form, scale, stereotypes, self-awareness, number of people, context, etc. – are each a map layer illuminating different aspects of the territory.

Dealing with Dominator Behavior is also a Territory

Just as we need multiple maps to understand the territory of dominator behavior, we'll need to map out multiple approaches to address it effectively.

My description (territory boundary) for dealing with dominator behavior is:

Acting to reduce the adverse consequences of dominator behavior.

Clearly, there’s no one-size-fits-all action here. Dealing will be as complex a territory as the dominator behavior it addresses.

Exploring that territory and building up a meaningful, effective toolkit of actions – where the diversity of the actions matches the diversity of dominator behavior – is what we'll be doing in the rest of this series of posts.