[This is part of BFNow Self-Study Module 5: Collaboration. For more about the overall Self-Study program, please look at About BFNow Self-Study and BFNow Self-Study Orientation.]

If you haven’t done so already, let me encourage you to pause, relax and release, perhaps with a big stretch or three deep breaths.

The goal of this lesson is for you to explore the territory of decision-making for groups of collaborators.

Let’s start.

Decision-Making

In any group, one of the most important questions is, “How shall we make decisions?” – kind of a meta-decision!

I’ve come to feel that there are four important criteria that we can use to assess any decision-making process. Generally, we want decisions that are timely, wise and supported, and we want the process to be efficient.

Timely – Many decisions happen in a context where the decisions need to be made within an externally imposed timeframe. If a house is on fire, decisions about how best to fight the fire need to be made quickly. A timely decision is made within its appropriate timeframe.

Wise – I know of no magic formula to guarantee wise decisions but decisions made while in your optimal zone and that use a systems perspective (to, for example, understand the context of the issue and the ramifications of a decision) generally lead to better outcomes. Does the process include these and/or other wisdom-enhancing components?

Supported – Many decisions impact more than one person – and even within one person, they impact more than one sub-personality. Do the multiple people (or sub-personalities) who will need to carry out the decision at least consent to it? If not, there are numerous ways to subvert an official decision so that the result is like pushing string.

Efficient – How much time and resources were required to reach the decision? Are those proportionate to the scope or impacts of the decision? Could another process have been equally timely, wise and supported and yet been more efficient?

Applying these criteria depends a lot on the specific context or situation. I have yet to see any decision-making process that is the absolute, one-size-fits-all best process.

Let’s look at a variety of approaches from the perspective of these four criteria.

Within each individual

Whatever the group decision-making form may be, at some point it depends on the process within one or more individuals. With the goal of making wiser decisions, I expect Planetary Era cultures to emphasize two approaches that are not so common in at least mainstream contemporary culture.

Decide from your Optimal Zone – The Enlightenment, which gave birth to modern democracies, thought everyone was “rational” except for a few crazy people. I expect the Planetary Era to have a more nuanced understanding of our complexity and see the value of doing Optimal Zone hygiene (silence, breathing, stretching, etc.) before making any considered decision.

Get input from your whole being – Your conscious mind and the sub-personality currently acting through it are only a small part of your total being. Whether your map for this larger territory describes it in terms of subconscious, intuition, gut feelings, body awareness, and/or sub-personalities, I expect Planetary Era groups to develop ways to get input from the whole of who we are. There are many insight-evoking creativity techniques that can be used, some as simple as going for a walk or sleeping on it. Similarly, imagine convening an inner round-table conversation among your sub-personalities as you work on a significant decision. In addition, all the visual tools we’ve been using can be helpful both for individuals and for groups.

Please hold this expanded character of individual decision-making in mind as we next turn to the structures that can be used for decision-making in and for collaborative groups.

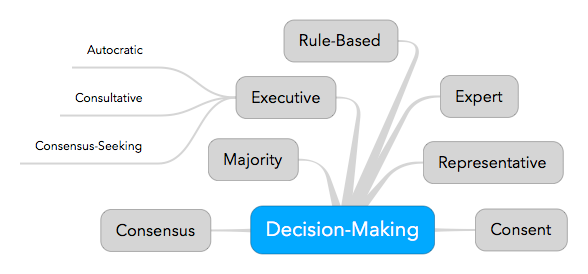

OK, on to various forms of decision-making, as summarized in this mind map.

Executive

I’m using executive to denote a process where a single person makes the decision. Like categorical thinking, this is our default for numerous mundane daily decisions and was characteristic of the Empire Era. And like categorical thinking, it has its place in the Planetary Era. It doesn’t go away; it just loses its near monopoly. I’d like to distinguish among three different types of executive decision-making:

Autocratic – This is pure single-person decision-making. It scores well for timely and efficient but is much more mixed for wise and supported. It makes sense in emergency situations where the person making the decisions has training and the respect of others in the group. The fire chief at a fire is a classic appropriate example, even in the Planetary Era.

Consultative – When there is not quite so much time pressure, the executive decision-maker can improve the likely wisdom and support by reaching out to others with relevant knowledge. Such experts need not be the same as those who will carry out the decisions. A lot of executive decision-making in business follows this pattern. How well it works, especially relative to alternatives, depends entirely on the situation.

Consensus-Seeking – When there is a stronger need for support, the executive can consult with those who will be affected and/or need to carry out the decision and attempt to forge a consensus. This is generally a hub-and-spokes process where the executive at the hub still makes the ultimate decision. If done well, it can have strong support.

It is easy to see the abuse of executive decision-making in the world around us but we shouldn’t let that blind us to its appropriate application in so much of daily life. This gets confounded by the strong association between executive decision-making and the controlling personality style. The dynamics between the controlling style and the leaving, enduring and performing styles makes those styles in us particularly wary of executive decision-making. Our challenge is to consider executive decision-making from an Optimal Zone perspective and then explore its right use.

Rule-Based

The Enlightenment period in Western history attempted to replace arbitrary executive decision-making (“the rule of men”) with decision-making based on agreed standards (“the rule of law”). Confucianism in China made a similar attempt even earlier. This pattern continues in bureaucracies around the world. Both movements did a lot to curb the abuse of arbitrary individual power although they replaced it with a more class-based abuse of power. They also did not completely remove individual decision-making from the process since laws and regulations must still be interpreted in each situation.

Frequently this process is neither timely or efficient and is resisted by those who bear the brunt of the regulation. It works best where those who need to follow the rules also support those rules and can largely self-regulate. Society is hardly there yet, but self-regulation based on agreed upon rules can work well in collaborative organizations.

Expert

If you are building a bridge, you want a skilled civil engineer involved in the design. In today’s world there are many decisions where expert knowledge is essential. Such decision can ideally be timely, efficient and wise. They can also be supported if the experts are respected. On the other hand, these decisions can be narrow-mindedly based on only the aspects of the situation within the scope of the expertise and thus blindly unwise. Expert-based decisions are generally best when held in a bigger picture formed by a more diverse group.

Majority

The opposite of expert decision-making is decision-making that gives every person an equal voice regardless of his or her knowledge about the issues. The most common of these processes is majority rule, which has become the default alternative to executive decision-making. It’s justification is that it’s better than minority rule (“Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others.” – Churchill) but it tends to lead to polarization and embittered minorities. As a process, it encourages developing proposals only to the stage where they can get majority support, which makes them less wise and less supported than they could be. It also doesn’t get good marks for being timely or efficient. Nevertheless, it is the standard that alternatives are measured against. I’m not sure where it might be an appropriate choice in collaborative groups but I wouldn’t want to categorically rule it out.

Representative

One way to strike a balance between majority rule and expert decision-making is to elect representatives who can become knowledgeable on the issues that need to be decided. For larger groups, such a system is more timely and efficient than doing everything by direct democracy and can be wiser. The representatives can also potentially use alternative decision-making processes, not just majority rule. I see representation in use as a practical matter in many existing collaborative groups.

Consensus

One long-standing alternative to majority rule is consensus, where everyone in a group must agree with the decision before it is made. One strength of this approach is that it forces the refinement of proposals until everyone is on board. Another is that decisions should have strong support. For a long time, consensus was the favorite decision-making process in intentional communities and ecovillages, places I see as important cultural laboratories.

However, over time it has become clear in many communities that consensus becomes the tyranny of the most chronically fearful. All of the processes we’ve described so far implicitly assume that the decision-makers are, in Enlightenment terms, rational – in our terms, in their Optimal Zones. That’s simply not realistic.

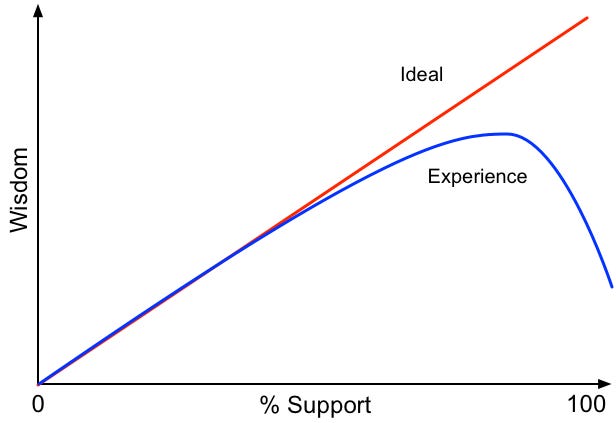

Part of the theory behind consensus is that the more people in agreement with a decision, the wiser the decision. In practice, it often doesn’t work that way because of those in the group who aren’t able to be in the present and who react to the issues at hand as a re-enactment of past traumas. We all do this to some extent, depending on the issue, and when we do, we have a defensive reaction, like the defense patterns in Module 3, and our judgment is clouded. Schematically we can represent this weakness of consensus like this:

In other words, while the expectation was that more support = greater wisdom, the experience has been that wisdom often peaks somewhere below 100% support. Just where it peaks, and even if it peaks, is situation specific.

Consent

In response to the limits with consensus, many intentional communities are turning to a practice called sociocracy. This is not the place to go into all of the aspects of sociocracy. For our purposes here, the key factors are

Every group and subgroup needs a clear statement of its vision, mission and aims (common ground). This is just good organizational practice.

Policy decisions within the scope of some subgroup need to have the consent of everyone in the subgroup. Sounds like consensus but it isn’t quite because of the next item.

You can only withhold consent on the basis that you can make the case that the proposal is in conflict with the vision, mission or aims of the group. It is not a matter of personal preference.

Proposals are developed with everyone’s involvement so by the time the proposal comes to a decision, everyone’s been heard. Because of this focus on co-creative design for the proposal, the decision is often just a formality.

In a way, the message of sociocracy is that the methods we use to develop proposals are at least as important as the methods we use for decisions. The ground we have covered in the first four modules could enable BFNow graduates to take the art of co-creative proposal design to a whole new level.

I’m not suggesting that sociocracy is the one size that fits all. Nor is it the only interesting model in use for collaborative groups. Rather, the example of sociocracy offers hope that in the Planetary Era we may be able to go beyond Churchill’s witty pessimism.

Experiential

Start these in the morning, carry them through the day and add reflections to your journal at the end of the day.

Make a list in your journal of the kinds of decision-making with which you have direct experience. It could be kinds from this exploration or something else. Notice how you make “little” decisions in the flow of your daily life as well as “big” decisions, both in groups and personally. Observe the diversity in your territory of decision-making.

Which of these have worked well and in what situations have they worked well?

How do these success stories relate to timely, wise, supported and efficient?

Are there any patterns you see in the success stories?

As with yesterday, if you are currently part of a collaborative group and the others in the group are open to this, share this exploration with them and use it as a starting point for consciously exploring your decision-making.

If you have questions or comments, please post them here.

Thanks,

Robert

[Link back to the Module 5: Collaboration Overview page.]