[This is part of BFNow Self-Study Module 4: Systems & Habits. For more about the overall Self-Study program, please look at About BFNow Self-Study and BFNow Self-Study Orientation.]

If you haven’t done so already, let me encourage you to pause, relax and release, perhaps with a big stretch or three deep breaths.

Today we start exploring systems, especially systems in which there is a flow of cause and effect, of influence and consequence.

The goal for this module is for you to become comfortable, in a practical every-day way, with using systems thinking and systems tools so that you can better understand how the systems around you work and how to fruitfully engage with them. I’ll be assuming that you’ve read Systems & Habits Overview, watched the videos and settled on your diagramming tools.

An important part of that goal is for you to PLAY. There is no one right way to use system tools and they exist to support YOU. Feel free to use these tools in whatever way feels most comfortable for you.

The goal of this lesson is for you to get more adept at creating and evolving your own system diagrams. If you are already comfortable doing this, great. If this feels new, I want to assure you that it’s simpler and more common-sense than you may imagine. The “magic” doesn’t come from it being about something mysterious called systems. The magic comes from the support these diagrams give to thinking with your whole brain.

You’re going to have a lot of options in this module. You can work on paper and/or electronically and you can work on some habit and/or another system of your choice.

Let’s start.

A system is …

First, a little bit of review from the Systems Literacy presentation:

As I’ll be using the term here, a system is a human construct – a map – intended to represent some aspects of a territory, that has

parts (or nodes)

relationships among the parts (or connections)

a boundary

a context outside the boundary

the option to have nested subsystems.

(In common speech people often also use system to refer to a territory itself such as the solar system. If these two usages start to feel confusing, just drop the word system and go back to maps and territories.)

Schematically, we can illustrate all of these possible components in a diagram that looks like this:

You can think of a system as a generalization and abstraction from a geographic map, similar to the way that a category is an abstraction from an object. In Module 2 we already used map in this abstract sense so Module 2’s map is essentially Module 4’s system.

In a geographic map, the parts are places and the relationships are spatial. In a system, the parts can be many different things (e.g. people, processes, events, psychological states, etc.) and the relationships may be about things like time or influence, but symbolically presented visually.

I’d like to continue to use the definition that I used in System Literacy, Part 1.

A system:

is an interface between us and the world that uses our whole brain to bring useful order to the overwhelming complexity of reality without oversimplifying

has three primary aspects:

○ diagram(s) that show the overall structure of parts and connections [visual]

○ descriptions of the various parts and connections [linguistic]

○ dynamics that model how the parts and their interactions change over time [kinesthetic]

It is the integration of visual, linguistic and kinesthetic – drawing on the strengths of each – that gives systems thinking its real power.

Creating your own system diagrams

Why go to all the trouble of drawing system diagrams? Most of the time our thinking-fast and our categorical thinking work just fine, but when they don’t, we need the greater mind-power that comes from thinking-slow. Thinking with systems is thinking-slow at its best since it uses the whole brain. Thinking with systems lives on our growing edge.

When and why create a system? Here’s a good start: Whenever you are …

dealing with more than the 4 chunks that working memory can handle

designing a new project

confronting a perplexing issue

needing a shared understanding

resolving conflicts

delighting in discovery

How to actually start? For this module, we’re providing you with a starting-point diagram to work from but what do you do in normal life when you may be starting from scratch?

You have a lot of choices – all of them good. You can start drawing, on paper or electronically. You can take inspiration from other system diagrams. You can make lists. You can put ideas on post-its.

Yes, you say, but what ideas? Start by naming the issue that is at the heart of your system. If you are looking at a habit, name it. Then work in both directions from that named part:

what are the inputs/influences that come into that part

what are the outputs/influences that come out of that part

Build a tree-diagram in both directions. Go one or two levels for a start. Once you have some inputs and outputs around your central idea, look for feedback loops that might connect something in the output to something in the input, but don’t force it. A linear system is fine if that gives a good representation of the territory.

Overall, start simple. Remember from the Systems Literacy video how the Habits diagram started with just three parts: cue, routine and reward. It evolved from there and we’ll evolve it even further in this module – and that’s a typical pattern. Expect your system diagram to go through many iterations as you learn more about the territory it represents. (This is another way in which systems are dynamic!)

The main thing is just do it. There is no one right way. You are free to create your system diagram however you like as long as it meets your needs, including giving you fresh insight.

Habits

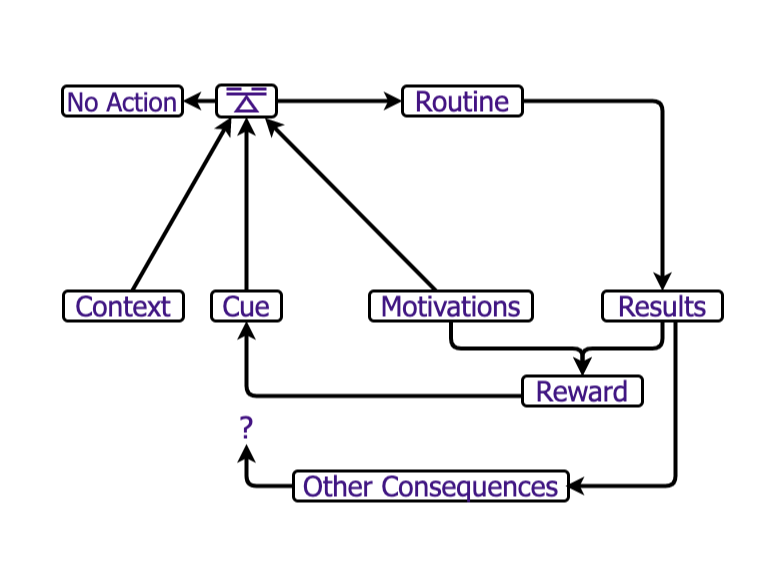

For this module, we have a specific topic and starting-point diagram. We’re going to use the territory of habits to provide examples for working with systems and system mapping. You’ll be able to start with the following diagram, which is an evolution from the habits diagram that I used in Systems Literacy, Part 2, starting at 9:52.

Let’s walk through this so you can understand the various parts and connections, starting with the …

Cue – This is whatever immediately prompts you to start another instance of the habit. If the habit is snacking, then the cue might be a body sensation, seeing a picture of food or walking into the kitchen. It’s effectiveness will be strongly influenced by the …

Context – This is all the immediately surrounding conditions. For example, you are more likely to snack if snacks are immediately available. The Context combines with the Cue in the …

Tipping Point symbol –

This is the decision point. Is the Cue strong enough and is the Context right? How do you judge this? It’s based on your …

Motivations – What desires and intentions are connected to this habit? The Cue and Context are somewhat objective while your Motivations are what you subjectively bring to the habit. Your Motivations can be complex, some supportive and some opposed to the habit. They influence both your choice to start the Routine and your reaction to the Results of the Routine. If the combination of Cue, Context and Motivations don’t align, the outcome of the Tipping Point will be …

No Action – Not every Cue leads to the active expression of the habit. But if Cue, Context and Motivations do align, you start the …

Routine – This refers to the set of behaviors and/or thoughts that you would normally think of as “the habit”. It leads to …

Results – These are the direct objective outcomes from the Routine. If you snack, you have, for example, taste sensations and new chemicals in your blood stream. The Results contribute to the …

Reward – This is your emotional response to the Results. This response may be complex, involving both positive and negative feelings. How you respond to the results will be strongly influenced by your Motivation. In your mind, the Reward gets associated with the habit and in particular with the Cue. If the Reward is felt as positive, it reinforces the Cue. Yet the Reward often isn’t the only outcome from the Results. There are often …

Other Consequences – This represents all of the secondary outcomes from the Routine/Results that aren’t seen as Reward. Often these are things we ignore or don’t notice. For example, the snacking may lead to poor nutrition or weight gain. The connection coming out of Other Consequences leads to a ‘?‘ because we may not associate these with the habit and thus they may not feed into the Cue. Making the connection from previously ignored Other Consequences into the Cue is often a great strategy for changing a habit pattern.

As you use this diagram, you’ll be replacing these generic descriptions with descriptions that are specific to whatever habit you are mapping, just like Josie did in her demo. You may wind up extending the diagram with new parts and connections.

Experientials

Choose whichever one appeals to you (or both):

Choice 1 – Habits

Choose a habit that you have and want to change or a habit you would like to have.

If you want to work on paper, print out the habits pdf. You can also work electronically by using some kind of diagramming software. Check this module’s overview page for the latest details.

However you do it, start personalizing the diagram. Replace “Routine” with the name of your habit (or place it next to “Routine”). Replace the other terms with your specifics or add them next to the other terms on the diagram.

○ What is your cue?

○ What’s the context?

○ What results come out of the routine?

○ What reward(s) do you feel?

○ What’s your motivation?

○ What other consequences are you aware of?Throughout the day, notice everything you can about this habit. Make notes in your journal.

Start looking for places and ways you could intervene in your habit system to change it in the direction you would like to go.

At the end of the day, add what’s appropriate from your notes to the diagram.

Choice 2 – A New System

Choose a project/issue/interest in your life that you would like to explore as a system.

Draw a simple initial diagram for that system.

Gather ideas/insights about the parts and flow of relationships within the system throughout your day.

At the end of the day, evolve your diagram and add notes to it.

We will continue to build and evolve these diagrams throughout the module.

Thanks,

Robert

[Link back to the Module 4: Systems & Habits Overview page.]