[This is part of BFNow Self-Study Module 6: How Change Works. For more about the overall Self-Study program, please look at About BFNow Self-Study and BFNow Self-Study Orientation.]

Let me encourage you, if you haven’t done so already, to pause, relax and release, perhaps with a big stretch or three deep breaths.

This exploration dives into the main process at the heart of cultural evolution with the goal of seeing how we can use it to influence that evolution.

Innovation as a territory

Time to take a closer look at innovation:

A bit of history – The earliest use of the English word innovation was apparently around the time of the Renaissance. It initially meant “restoration, renewal” but came to mean “a novel change, experimental variation, new thing introduced in an established arrangement.” I like thinking of it as something that is both truly new and that revitalizes the larger system that it enters into. In this sense, true innovation is nourishing as well as novel.

In the eyes of the beholder – What’s the difference between an innovation and a refinement, an adjustment or a modification? It’s all up to the observer. When is something a group of innovations rather than a single innovation? Again, it’s up to the observer.

To say something is an innovation is to express the belief that, in some meaningful way, it creates a new category. It’s an assertion about more than the individual instance. To make that assertion, you need to be knowledgeable about the broader territories to which this innovation could belong. However, even with the benefit of expertise, expect “innovation” to be a fuzzy concept – useful but with grey areas.

It’s not always a good thing – So far I’ve been talking about innovation in general as a good thing. That’s consistent with the broader culture’s pro-innovation bias but I don’t mean to be so uniformly positive. Indeed there are many things in our world today, like persistent pesticides, that were at one point innovations and that I would rather had never come into wide use. More generally, many innovations involve trade-offs, the full scope of which don’t become clear until they are put into practice.

So I suggest we take a neutral view of the value of innovations, recognizing that each innovation needs to be assessed on its own merits. That said, the good ones and the bad ones both spread in similar ways, so innovation is still a useful overall concept.

Nevertheless, we need them – Completing the transition to the Planetary Era will require new cultural patterns – new cultural DNA. So while we need to be discerning about what innovations we encourage, innovation is a territory we need to get good at working with.

How innovations spread

By decree – If the CEO of a company establishes a new, innovative policy, everyone in the company is expected to follow it. If the government passes an innovative law or creates an innovative regulation, everyone is expected to abide by it. On the surface this looks like a great way to spread an innovation. It can work well if those who need to follow the decree are at least neutral towards it, but never underestimate the ability of humans to subvert or get around an imposed requirement that they don’t like. In addition, anything established by decree can be removed by decree. The next CEO or the next government can undo whatever the current ones have done.

In addition, decree-spread innovations miss the opportunity to learn and mature via experience.

By diffusion – The other main way that innovations spread is by voluntary adoption. Information about the innovation travels in many ways – from word-of-mouth to various media. This process may seem slower than by decree but, with voluntary adoption, the results tend to be more enduring and the process less prone to conflict. It is also a process that anyone can use – you don’t need to be in a special role.

As far as I know, it is the main process by which evolution moves through a complex adaptive system.

The study of the diffusion of innovations began over a hundred years ago, got a notable boost in the 1920s and 30s as rural sociologists studied the uptake of new farming techniques and got firmly established with the publication of Diffusion of Innovations by Everett Rogers in 1962. Since then it has influenced many different fields – from academic areas like sociology and anthropology to business concerns such as marketing and product development.

I’ll describe Rogers’ framework in the next section. Before doing that, I’d like to turn to an example.

An example – One of the most significant worldwide cultural changes in the past few decades has been the spread of electronic information technology. This has involved a steady stream of innovations, building on one another, and the spread of their use. A good indicator for that spread is the percentage of the world population that is using the Internet (see here for more data)

In the relatively short span of 30 years, more than 50% of the world’s total population (all ages) is now using the Internet! Compared to previous cultural changes, the extent and speed of this is astonishing – and it shows what’s possible in the 21st century.

This qualifies as a major cultural change because communications and linkages are core to any complex adaptive system. The value and impact of this change is complex but that’s not my focus at the moment. Rather, this is a classic example of the spread of, in this case, multiple related innovations by diffusion.

Strategies

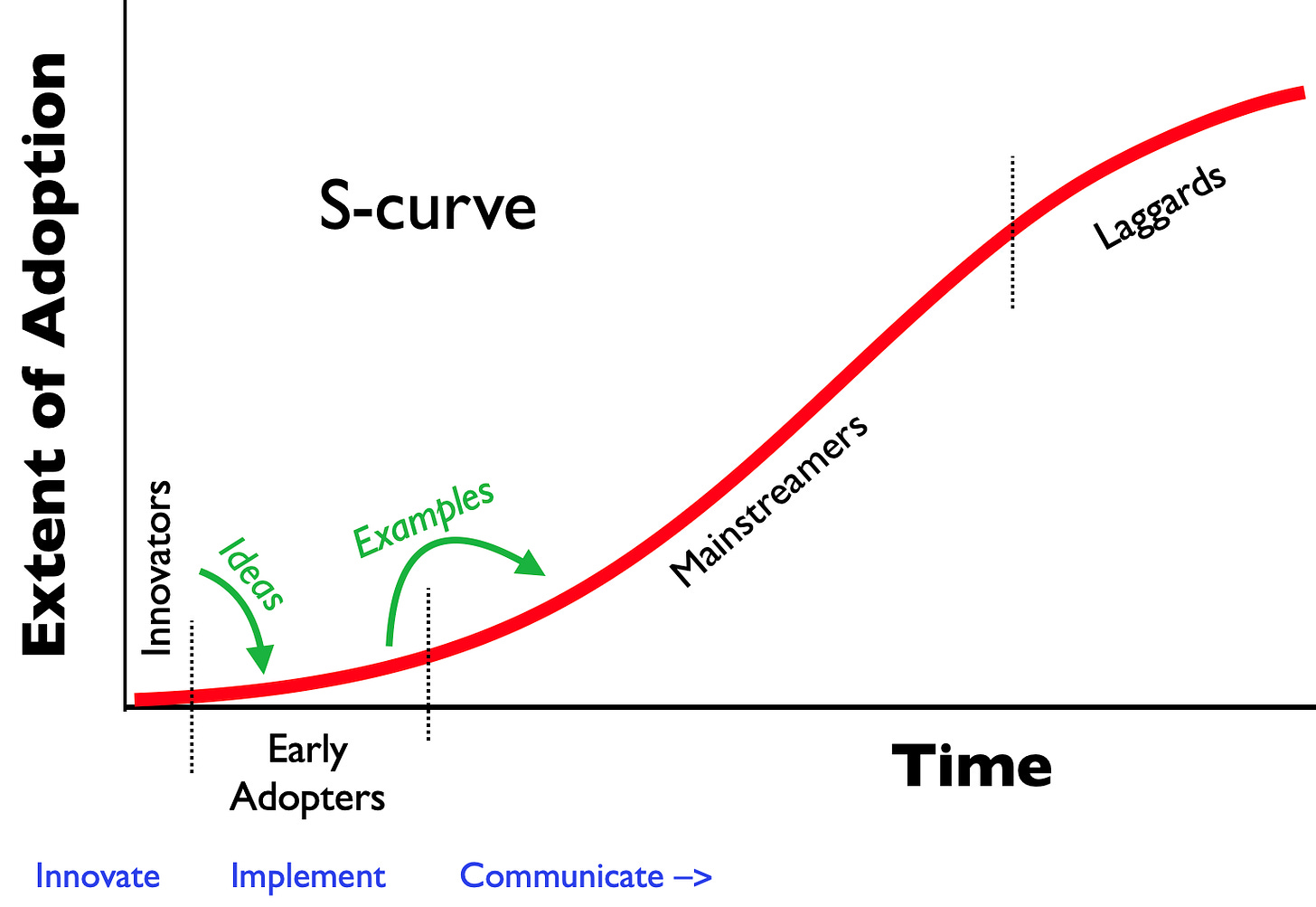

How does diffusion work? I’d like to explore this question with the help of this schematic diagram:

The red S-curve shows the way that increasing numbers of people adopt an innovation over time. The curve starts at zero and rises to whatever maximum adoption may be possible for this innovation in whatever population is being considered.

Along the way, the character of the people who are doing the adopting changes:

Innovators – At the very beginning is the person or people who bring the innovation into being. They are often independent thinkers, even a bit eccentric.

Early Adopters – The first people to respond to the innovation tend to have similar interests and worldviews to the innovators’, although they are more connected into the culture. They are well networked, interested in trying new things and tolerant of the risks involved. They are often respected by Mainstreamers, who see them as opinion-leaders. They respond to ideas. For example, they may be willing to make their own version of the innovation just on the basis of an article they read.

Mainstreamers – Rogers divides this group into Early Majority and Late Majority but I’m content to keep them together. Mainstreamers are even more identified with the culture but not as well networked as the Early Adopters. They tend to be focused on their personal lives and look at an innovation through a “what’s the benefit to me?” lens. They are skeptical of ideas and want to see examples, preferably where someone they respect has already adopted the innovation.

Laggards – These may be people who just don’t like change or they may be actively opposed to the innovation. I’ve been happy to be a Laggard relative to Facebook.

Just as we need to take a neutral view of the value of innovation, so too we need to avoid assuming that it’s good to be in any one of these categories. Your placement in these categories depends on your relationship to the specific innovation. I am an Innovator for some innovations, an Early Adopter for others, a Mainstreamer or a Laggard for still others.

Just as the character of the adopters changes along the curve, so also the strategy that that change agents can use to most effectively promote the innovation needs to change along the curve:

Innovate – When something is just being birthed, it’s important to have a safe space to innovate without much external attention. The new idea may emerge fully formed but often it goes through many changes and much development in its very early stages. You are building new DNA. Focus on its quality and leave the question of its spread and reproduction to later. This is the time for prototyping.

Implement – Once the innovation has had its first tests, it’s time to share it with the sympathetic world of Early Adopters. As they put it into practice, they will make refinements and additions to fit with their context. This is the time for diverse pilot projects. The result will be a more robust and mature innovation and a better understanding of how to implement and use it. This is also the time to start putting in place whatever infrastructure may be needed to support the widespread adoption during the Mainstreamer phase.

Communicate – As the Mainstreamer phase begins, the Early Adopters need to shift from focusing on implementing to focusing on being opinion leaders, sharing what they have learned during implementation. This is also the time to get the innovation out to the public via various media. It’s important not to rush this. If you go public before the implementation phase has worked out the bugs, you can create a bad reputation that will “vaccinate” the public against what could otherwise be a useful innovation. This happened to rooftop solar hot-water heating in the 1970s.

You will notice that I’m giving the most attention to the first quarter of the curve. This is the phase where innovations need the most help and where change agents can have the most impact. It comes before the world around you has much of a clue as to what you are doing or why it might be important. It can feel lonely, which discourages people from hanging out here. Bright Future Network is designed to help overcome this and make it easier to support budding innovations when they really need it.

Finally, I encourage you to look back at the Internet Usage curve. The start looks like an S-curve but the top hasn’t turned over yet. If it proves to be an S-curve, the world will likely be at about 3/4 adoption by 2030. Each innovation that supports this curve has gone through its progression of Early Adopters and Mainstreamers, spreading across geography as well. A young student from Africa might be a Mainstreamer while studying in Europe but then becomes an Early Adopter to their surrounding community back home – and that’s how the use of the Internet diffuses.

Experiential

Think of some societal issue that’s important to you and explore how that issue could be addressed through the kind of Innovate-Implement-Communicate approach described here.

What are the cultural innovations that would be helpful for this issue? Are the steps small enough to be doable? If not, what’s a smaller step that might work? How/where/with whom would you prototype it?

Are there helpful innovations already underway that you’re aware of? Where are they along the diffusion curve? Are they in the Innovate, Implement or Communicate phase? Based on where they are, what do they need to continue their journey?

As you consider these, it’s important to not rush the diffusion process. Don’t fixate on big outcomes but find incremental next steps. As usual, use your journal to capture whatever feels useful.

If you have questions or comments, please post them here.

Thanks,

Robert

[Link back to the Module 6: How Change Works Overview page.]