Hugged, Heard or Helped?

A simple practice for a brighter interpersonal future

My wife, Lianna, recently came across the lovely question "Do you need to be helped, heard or hugged?" It's a question that can be asked of someone when they're upset. It's a simple process that could be very helpful for many couples, as well as others. We quickly recognized this as a great example of Optimal Zone first aid that is savvy about psychodynamics. We were intrigued to add it to our toolkit. So, as we try to do with any new first aid before we need it, we talked about it, practiced it and agreed to use it.

In this post, I'd like to share what we've done and then add more depth by looking at the principles and science behind it so that if you decide to try it, you can use it flexibly and well.

As a simple practice

Our main adaptation (for reasons I'll describe below) was to reverse the order. Having done that and made it part of our toolkit, now if one of us notices that the other is upset, we can ask "Hugged, heard or helped?" and the upset one will understand the meaning and intention of the question. Likewise, the upset person can simply come to the other and say one of those three words and the other person will understand. This works best if the upset isn't about the other person. There are better processes for that case, like the Gottman Regrettable Incident Process.

Of course, we aren't limited to only one choice. We can, for example, start with a hug, move on to hearing the upset person and once that's complete, if the upset person requests it, the other can offer the requested help. The important thing is that the upset person gets to choose where to start and what else, if anything, to do beyond the first choice.

Going deeper: principles and contexts

That may be enough description so that you could use it as a practice but it can be used more skillfully and adapted more appropriately within the frameworks of humanOS literacy and being savvy about psychodynamics from the Foundational Keys.

While it's a great practice in the right setting, it's not a good fit for all contexts. It seems to be especially popular with adults who are working with young children, like elementary school teachers, and in some counseling settings. Translating that experience into the world of free-form adult-to-adult interactions, as I'm doing here, is certainly possible but it benefits from some care and sensitivity.

Helpful principles

When a person is upset, their nervous system is in a reactive state after some triggering event. They feel less safe than they would like and are looking for a pathway back toward their Optimal Zone, where they will feel more safe. If they are upset in an agitated way, they are likely in a sympathetic activation. If their upset is more depressed and heavy, they are likely in a dorsal vagus state.

In either case, they are feeling out of control and with less agency than they would like. They are likely to feel somewhat overwhelmed, exacerbated by having less mental capacity than they would in an Optimal Zone state. They might not use this terminology to articulate their feelings, but these are helpful ways of understanding the process from a humanOS and psychodynamic perspective. Offering choices to the upset person supports their sense of agency and allows them to have some control over the support they get. Also, they are likely to know better than the support person what they're open to and what would be genuinely helpful.

The role of the support person is to help the upset person to find their way back towards greater safety. You are not there to do it for them. Key virtues for the support person are kindness, patience, non-judgment, attunement to the upset person and a willingness to follow their lead.

It's important for each person to feel safe with the other and with the process. It's a big help to discuss, get comfortable with and agree to the process before it's needed. It's important for the upset person to feel they can be fully honest in their responses to the question – including saying "Not now."

So the core principles for this process are safety, agency and genuine consent.

The ANS context

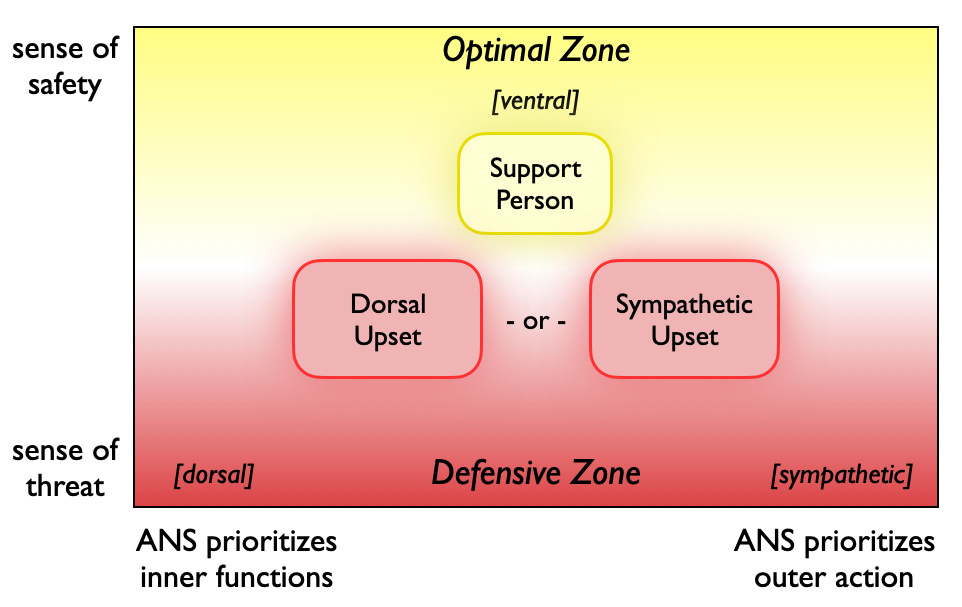

Let's now go a bit deeper and look at this from the perspective of the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) with the help of the following Optimal Zone/Defensive Zone diagram that builds on my post about Your Optimal Zone:

The diagram in general is a map of the full range of Autonomic Nervous System states. The areas I've marked are the regions of ANS states that each of the two people are likely to be in for the process to work well. There are two possibilities for the upset person since we need to be able to treat a dorsal vagus upset somewhat differently than a sympathetic upset.

The support person is ideally in the middle of the Optimal Zone – in a calm, clear-headed, present state. They aren't in either a ventral-dorsal blend (deeply relaxed) or a ventral-sympathetic blend (strongly energized). In the middle puts them in the best place to be relational and compassionate. I suspect it would be challenging to get this approach to work well if the support person was in the Defensive Zone, especially if they were on the same level or lower than the upset person.

If the support person is not as clear-headed and present as they’d like to be when the upset person arrives, it would be helpful for them to take a moment to breathe, shift their focus or do whatever helps them move to that middle place in the Optimal Zone.

The upset person is in the upper half of the Defensive Zone. This approach isn't intended for the kind of more extreme sense of threat and activation that would lead to either an intense fight-flight response or a dorsal bodily shutdown.

These regions, close to the center of the diagram, are where many people spend much of their time in daily life. They provide the appropriate contexts for this process.

How the options work

Each of the three options points to a different step back towards safety, each valuable in the right setting.

Hugged

A calming, gentle hug is a great way to activate the ventral vagus branch of the ANS, thereby communicating safety directly into the body. Of the three options, it is usually the most direct and easiest way to help the upset person to move towards their Optimal Zone. We're wired for it. Contact on the front of the body is one of the primary ways that caregivers communicate safety to infants and young children, and our “inner child” still appreciates it.

However, some people may not feel comfortable hugging – perhaps for cultural reasons or because of associations with sexuality or simply because of how the upset person relates to the support person. As always, the principle here needs to be safety and genuine consent.

In addition, sometimes a simpler form of touch, such as holding hands or a gentle touch on the arm or shoulders, can be more appropriate to the situation. While not as generally impactful as a hug, this kind of touch can still be helpful and may be more attuned to the kind of support the upset person can actually receive.

Whatever the form, some kind of contact can be helpful for both dorsal and sympathetic upsets. In both ANS cases, a hug or a touch conveys safety and connection, reduces muscle tension and cortisol, increases oxytocin and can interrupt unhelpful mental cycling. In the sympathetic case, the effect is faster, more intense and more physiological. The dorsal case may benefit from a longer time in contact. It’s less dramatic but no less valuable.

Yet physical contact is not always the best first choice. An upset person may not be ready to release their upset until they have been heard or even helped.

Lianna and I chose to make hugging first on our list because we know its value to us, we're comfortable doing it with each other, and we know that we can deal with the issue behind the upset more effectively if we are both in or at least closer to our Optimal Zones.

If you do a hug, it's great if you hold it long enough to get to the point of a felt release of physical tension but it's even more important that the upset person sets the tone and is the one to decide when to end the hug.

Heard

There are many reasons for an upset person to want to be heard by someone with whom they feel safe. Their upset may have been triggered in a situation where they felt they couldn't fully express themselves and now they want to be able to do that. Or it could have all happened so fast that they didn't have time to think. They may want to tell their side of the story. They may want to sense and express their feelings in a safe, spacious setting. This may include crying or some other non-verbal expression. Or they may want to think out loud as they try to make sense of whatever upset them. However they want to express themselves, it should all be welcome.

Whatever the reason, it's important for the support person to understand that their role is just to be with, to witness and listen. It's not a conversation. If you're the support person and you think of things you'd like to say in response to what you are hearing, store them away in your mind but don't create the expectation that you'll say them soon. Often, when a person needs to be heard, they don't have the bandwidth to then listen and integrate whatever you might have to say, however wise or useful it might eventually be. If they do ask for your thoughts, still be careful not to overwhelm or drift off topic.

Helped

The upset person may want help for a variety of reasons. Their upset could have been set off by the frustration of not being able to accomplish something they feel should be possible. For example, they may be working with some computer program, trying to get it to do something but they haven't been able to figure out how. If the support person knows how, this can be an easy fix.

Alternatively, the upset person may want advice on how they could have approached the upsetting situation differently or what they can learn from it.

In either case, an upset person is more open to receiving help after they have had a chance to move back toward their Optimal Zone. They will have more useful mental functions back online to both solve problems and understand solutions. That's one of the reasons we put "Helped" last on our list of options.

The other reason is that support people, assuming they are in the area of the OZ/DZ diagram that I've indicated above, have a tendency to jump to "fix it" mode sooner than the upset person is likely to be ready. After all, the support person is relatively at ease and their problem-solving mental functions are working fine. They're ready to just "fix it." Putting the question last helps everyone remember to wait on helping until the upset person is ready.

To be most helpful, the help needs to be attuned to what the upset person can actually use. They have been overwhelmed and may still be, so long explanations may not be something they can assimilate.

In addition, the upset person is likely to feel vulnerable, and may feel defensive, self-critical, frustrated and/or stuck. Best if the help can be delivered in a way that is empathetic and normalizes that we're all always learning and doing things that we could improve on next time.

Adding this to your toolkit

I hope you’ve found this useful and will consider adding this practice to your toolkit. You can use this post as a starting point and then adapt it to your situation. If you have one or more people that you would like to share this practice with, feel free to share the post with them. If you make some adaptations that you find helpful, please let us know via a comment on this post.

Thanks!

thanks for this beautiful, simple tool. nice shorthand for support. cynthia