[This is part of BFNow Self-Study Module 2: Objects, Categories, Territories & Maps. For more about the overall Self-Study program, please look at About BFNow Self-Study and BFNow Self-Study Orientation.]

If you haven’t done so already, let me encourage you to pause, relax and release, perhaps with a big stretch or three deep breaths.

Today I’d like to share a few simple-yet-common mapping patterns / building blocks / metaphors that you can use with maps for territories of all kinds.

One powerful way to think of these is as alternatives to object as the metaphorical starting points for understanding a territory. As I’ve been using it, objects are non-overlapping units, bounded in space, whose characteristics attach to the unit as a whole, persist over time and are independent of context (object permanence). All of the types we will look at today differ from objects in one or more of these qualities.

This is a small sample of the rich variety of metaphorical starting points that are out there with more being invented all the time. It seems, in many ways, that we in the early days of a golden age of mapping, diagramming, data visualization and graphic representations of all kinds. Enjoy the possibilities!

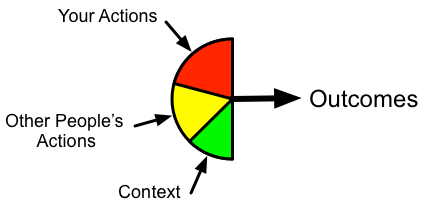

We’ll look at six types: composites, layers, sliders, spaces, fields and systems – and I’ve got icons for them:

Composites

I’m using the term composite for a map (or an element in a map) that represents a territory where there are multiple parts and, optionally, their relative size matters – so the icon is a pie chart. What we’ve already done in dividing the personality territory into sub-personalities creates a composite mapping. Mind-maps are generally composite maps. A composite map says, you need to understand the relationships among parts to understand the territory.

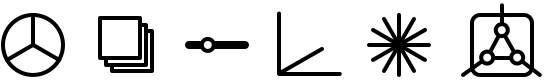

A commonplace example where composites apply is cooked food. Michael Ruhlman did a fascinating mapping of common foods in his book Ratio. Here’s one interpretation (from the no-longer-active tuscanfoodie.com site):

In this example, doughs & batters is the territory and each food (e.g. Bread, Pasta, etc.) is a composite drawn from the same set of ingredients (e.g. liquid, flour, etc.) but in different proportions as shown in the pie charts. Like a conventional category, this mapping groups the foods together based on their common features but, unlike a conventional category, the individuality of each food is maintained plus given more meaning by comparison to its peers.

Another place where a composite approach is helpful is with the issue of one’s personal ability to shape one’s life. It is common for people to think about this in categorical terms where you are either

responsible for everything (the mainstream legal approach) or

dragged along by forces beyond your control (an alternative philosophical approach but hard to put into practice).

(Notice how the either/or quality of categorical thinking is a generalization of the way that objects don’t overlap.)

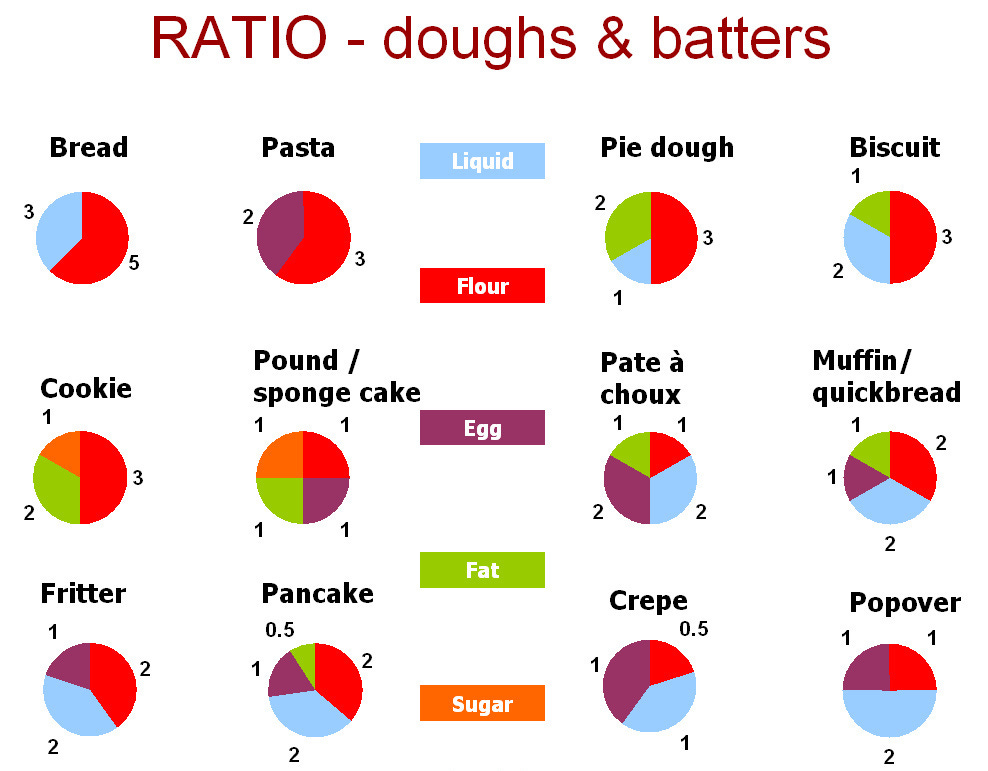

If we look at this issue as a territory, we are likely to see that the shape of one’s life is actually co-created, which we can map like this:

I’ve just arbitrarily sized the pie slices and they would be different in different situations. (It’s just half a pie to keep all the inputs coming in on the left.) If we wanted to map co-creation more thoroughly, we would have to include lots of feedback loops among these three inputs and time delays. I’m not going to do that here but just note that, even in this simple form, a composite map helps to communicate how, in co-creation, you have multiple influences rather than the categorical poles of absolute control or powerlessness.

Composites are unlike objects in that the parts and their relationships matter. The stable characteristics attach to the parts, not to the composite as a whole. The relationships among the parts may change from instance to instance, over time and in response to the context.

Layers

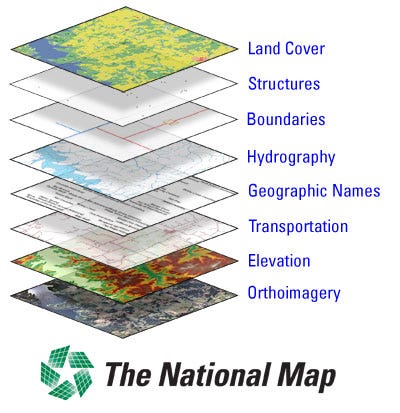

Layers are a lot like composites, except stacked instead of side by side. Layers have a long history in the world of geographic mapping as now exemplified by geographic information systems (GIS) that put different categories of information on different layers (which can be individually turned on or off) allowing a highly customizable composite map:

Layers are a good approach whenever the parts of your territory can be grouped so that similar elements are on the same plane yet the planes are different from each other. It doesn’t need to be a stack of spatial maps. I can imagine a layered map of sub-personalities where each layer corresponds to a different age in your life when that sub-personality first formed. It would be interesting!

Similar to composites, layers are unlike objects in that the layers and their relationships matter. The stable characteristics attach to the layers, not to the stack as a whole. The relationships among the layers may change from instance to instance, over time and in response to the context.

Sliders

A slider can be used to show the value of a simple variable, a matter of degree, anything that changes smoothly from some minimum to a maximum value. It’s used this way frequently as a user-interface element in software.

Sliders are the antidote to black & white thinking. My wife, Lianna, and I will often say, after we’ve used language that sounds like categorical polarities, “There’s a slider here.” That’s our way of reminding each other that language, by default, gets us to speak in seeming absolutes even when that’s not our intent. I hope you will develop similar language.

Sliders can be used for the relative mix of two overlapping layers, a composite of two, in a kind of double exposure. The two layers or composite parts correspond to the two poles of the slider.

A good example of mapping with a slider is the signal and noise demo from hOS Literacy Part 4, starting at 8:31. If you haven’t played with the demo on the website yet, I encourage you to do so. As you move the slider back and forth, the ratio of signal to noise changes – yet you can still recognize the signal over a large part of that range. Only at the ends of the slider’s range is it either pure signal or pure noise. In real life, it is rarely categorically one or the other.

You can reduce the level of conflict in your life if you get good at listening for the signal and filtering out the noise in what other people say. You will build common ground and mutual respect much more easily.

Sliders are unlike objects in that the poles have their own distinct characteristics. Indeed it is the characteristics of the variable being represented or poles being blended that are stable. The variable’s value or the poles’ blending may change from instance to instance, over time and in response to the context.

Spaces

If a slider allows us to express relative proportion along one dimension, spaces move us into multiple dimensions. Color, as discussed in hOS Literacy Part 3, starting at 15:47, is a great example of a territory that is well-represented with a multidimensional map. Language and the what pathway try to deal with colors as definable objects by imposing distinct names and categories but this is at best a crude approximation.

When we treat color as a territory, we find that it can be represented in all of its subtlety by continuous variation along three axes, such as hue, saturation and lightness. (If you haven’t yet, you might enjoy playing with the color demo on the website.) Color, in this sense, has no object-like bounded-in-space parts. Nature provides lots of similar examples that are better mapped smoothly along a set of dimensions than treated as objects.

Spaces are unlike objects in that each point in the space is different, they aren’t necessarily bounded, they aren’t in physical space, The stable characteristics are attached to the dimensions which then translate into unique characteristics for each position in that space.

Fields

Think here of things like the gravitational field or a magnetic field. They have no edge; they just vary from place to place and extend, in principle, throughout all of physical space. They can overlap and coexist in the same place. Fields can be good for mapping things like the spread of a rumor, so they have human as well as physics applications.

Fields are unlike objects in that they aren’t bounded, they can overlap, and they are specific to time and context.

Systems

I’m including this here to acknowledge that any map for a territory is a system, including all of the above examples. If none of those specific types apply to your territory, the default is a general system with a boundary, parts, relationships, a context and possibly nesting of subsystems.

In saying this, I am continuing to use “system” as a human-constructed interface composed of diagrams, descriptions and dynamics. It’s a kind of map, with map here understood in its most general and abstract sense, not just a geographic map. In this usage, systems are interfaces for territories, not the territories themselves.

Experiential

Look back at the map you started in the previous experiential. Using today’s ideas and examples, evolve your map (or create a new one).

Find opportunities throughout your day to consciously choose to approach certain things as territories with maps that use composites, layers, sliders, spaces, fields and/or systems. Break free of the hold that the object metaphor has on our minds. Practice using this language at least to yourself.

At the end of your day, reflect on your journey through objects, categories, territories & maps. Adds some notes to your journal.

If you have questions or comments, please post them here.

Thanks,

Robert

[Link back to the Module 2: Objects, Categories, Territories & Maps Overview page.]