[This is part of BFNow Self-Study Module 2: Objects, Categories, Territories & Maps. For more about the overall Self-Study program, please look at About BFNow Self-Study and BFNow Self-Study Orientation.]

If you haven’t done so already, let me encourage you to pause, relax and release, perhaps with a big stretch or three deep breaths.

For this module, we’ll start with objects and then categories and categorical thinking. From there, we’ll move on to territories & maps.

Objects

In everyday language, we speak of objects as things that exist “out there” in some reality beyond our minds. It’s a very convincing impression but it’s an illusion.

What we experience in our minds as an object is both less than and more than what exists “out there.”

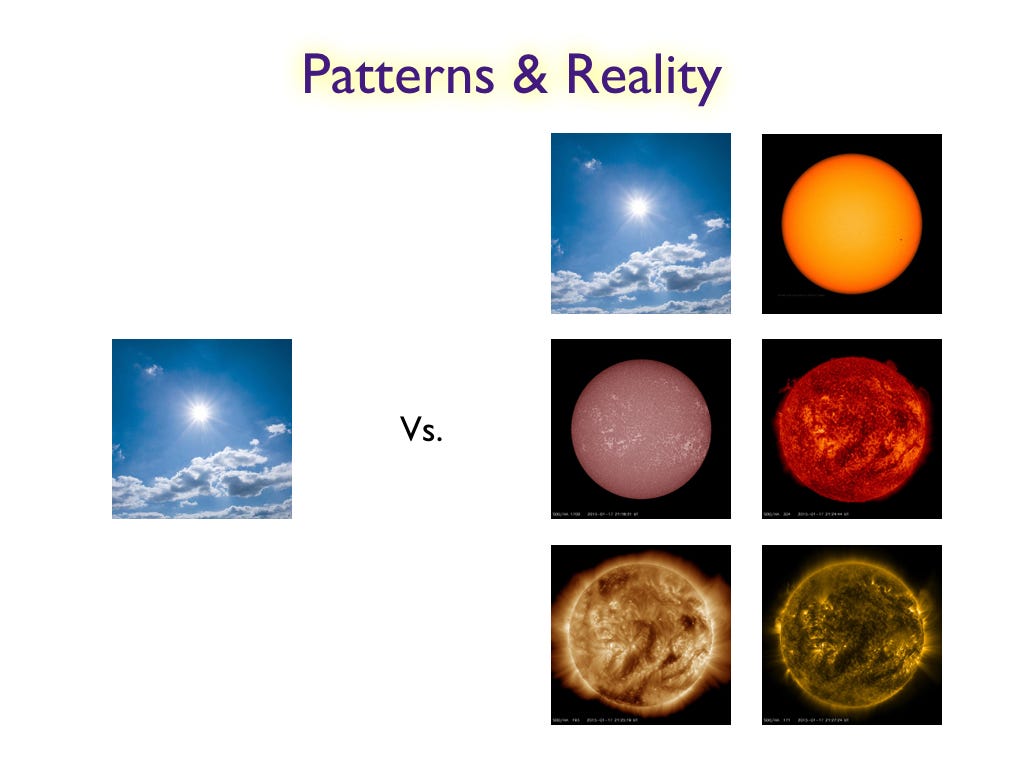

It is less than at least because of the limits of our senses. This was the point of the section about the sun in hOS Literacy Part 4, starting at 14:42:

The bottom four images on the right are what the sun “looks like” in the ultraviolet, outside of the visible part of the spectrum.

So what we experience in our minds as an object is, in part, an incomplete representation of what’s “out there” (which I will just call a thing when I need to distinguish it from an object).

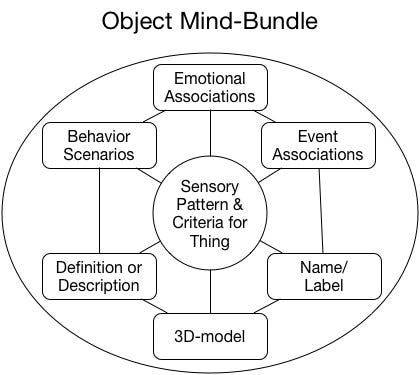

Yet an object is also more than the thing it represents because of all of our personal associations: emotional associations, event associations, internalized 3-D model, name, description and behavior scenarios. These all reside in us and not “out there,” yet they are an essential part of how we experience an object.

In effect, object perception is the original augmented reality technology and it’s so convincing we don’t normally notice that our raw perceptions are being augmented.

What we actually experience as an “object” is a mind-bundle. This is a term I introduced in hOS Literacy Part 2, starting at 9:39 and going to 12:35 and is a pattern of neural activations and associations that we experience as a unit. Here’s a diagram of some of the facets that our subconscious serves up to our awareness when we recognize an object:

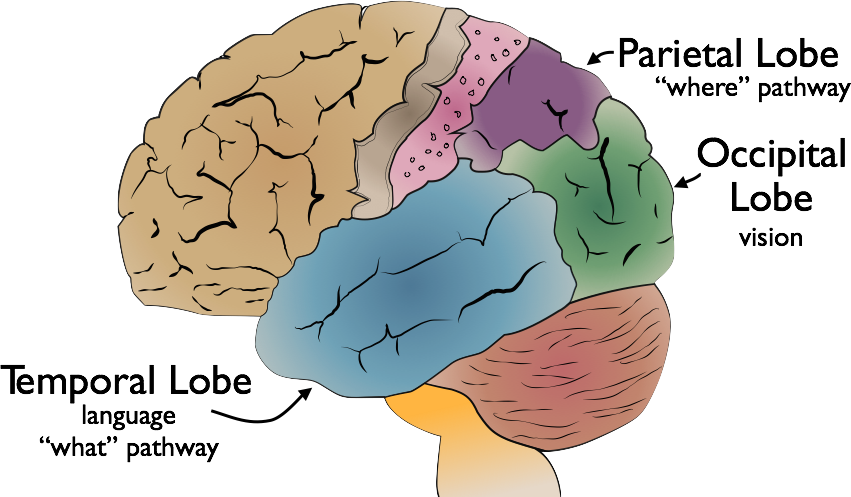

The current psychological understanding is that the brain does this conjoining of incoming sense data, memories and associations in the Temporal Lobe’s “what” pathway. This is also where incoming sounds are recognized as speech and given meaning. Indeed we can have object mind-bundles based on any of the senses: auditory objects, touch objects, perhaps even smell and taste objects, as well as visual objects.

The basic “what” pathway functionality is widely shared with other animals. Likely any animal with senses has it to some degree.

From an evolutionary point of view, the most important associations the “what” pathway makes with incoming sense data are answers to

how is this thing likely to behave and

how should I behave in relationship to it? Is it dangerous; should I avoid it? Is it nutritious; should I eat it? Can I make it useful? Should I ignore it?

In survival terms, the main point of being able to identify a thing is so that you can learn the behavior scenarios (its and yours) associated with the thing and act accordingly.

The “what” pathway’s long evolutionary history shows in the way it’s focused on speed of recognition and clear-cut responses. If you are walking along a trail, your brain needs to decide in a fraction of a second whether that linear thing ahead of you is a snake or a stick. This is a fabulous survival capacity but its stereotyping and lack of nuance become less useful when applied in less urgent but more complex situations, namely most of the challenges we face in modern life.

The “what” pathway excels at recognizing and serving up mind-bundles for discrete objects but it is not good at tracking dynamic patterns of relationships or overall context. For this we need the “where” pathway, but I’m getting ahead of the story.

How does our object perception emerge? Starting as infants, we organize our perception of the world around the core experience of objects – their characteristics and behaviors. When we are as young as 3 months, we humans recognize visual patterns as objects based on four characteristics:

Boundedness – objects have continuous, enclosing edges

Cohesion and persistence – all parts of an object move together along continuous paths

Exclusion – two objects can’t occupy the same space

No action at a distance – Objects only affect each other if they make contact

We develop the ability to recognize an object at different times and different places (object permanence) by abstracting our experience of the object out of its immediate context. Along the way we learn to give more attention to things than to the relationships among things.

We also learn to treat objects as a unit. We may use visual details to help with object recognition, but once recognized, we attach all of the associations to the thing as a whole. This stands in contrast to territories, where there is more interest in mapping the details of what’s inside the territory – but again I’m getting ahead of the story.

By the way, in this psychological usage, objects can be animate as well as inanimate. Indeed, an infant’s most important first object is its caregiver, usually its mother. With this as a metaphorical starting point, we generally see people – include ourselves – as units with a single set of characteristics, i.e. objects.

Experiential

For today’s experiential, I’d like you to experience objects as mind-bundles, that is, notice the rich, multifaceted associations that your subconscious serves up to you when you focus your attention on something “out there.”

Look around you at what you experience as a 3-D space filled with objects.

Stay in a largely nonverbal state of mind.

Let your attention rest on what you see as an object (such as a chair or book) so that its associations come into your awareness. A second or so is usually sufficient for the emergence of a rich set of associations.

Notice the direct associations and knowledge that are joined to what you see:

Does it feel like a 3-D object? Do you know or could you predict what it would look like from other directions, including faces you can’t currently see?

Do you know at least something about its use and purpose?

Do you have some level of affect (emotional reaction) that you associate with it, even if that reaction is mild?

Can you name it and include it in a meaningful sentence. Do you have a sense of what other words would seem to fit naturally with it and which other words would seem weird or humorous if used with it?

Can you associate any personal history with the object?

You likely could easily answer yes to all these questions once you chose to notice.

Move your attention to another object and take a second or two to allow your subconscious to call up the associations you have with this new object. How is the feel of this new object different from the first object?

Scan slowly around the room or space you are in and sense the incredible amount of information and meaning that your subconscious could serve up to your awareness if you were to trace even just the direct associations you have with all the things in that space. Psychologists have shown in many ways that all this information influences our actions even if we aren’t noticing it.

During your day, take a few more times to turn your attention to some physical thing and notice as much as you can of all of the information and meaning that it evokes for you. Sense the invisible, informational side of what we think of as objects.

Make some notes in your journal as you feel moved to do so.

If you have questions or comments, please post them here.

Thanks,

Robert

[Link back to the Module 2: Objects, Categories, Territories & Maps Overview page.]