Optimal Zone Resilience

Optimal Zone resilience is perhaps the single most important skillset you can learn to affect both your quality of life and your ability to contribute and collaborate.

It's all about learning how to partner with your autonomic nervous system (ANS) so that you can spend more time in your Optimal Zone, feeling qualities like curiosity, calm, clarity, connection, confidence, courage, creativity and compassion1 and less time stuck in your Defensive Zone, feeling anxious, threatened, angry or discouraged.

The state of our autonomic nervous system profoundly affects how we experience and navigate every moment of our lives, coloring how we feel and structuring what we're capable of. Its role is huge in everything from our behavior to our sense of who we are. It also has a profound effect on our health and longevity. Being Optimal Zone resilient is thus a life skill that can benefit everyone. A wise culture would teach it to its children. We're not there yet so we need to start with ourselves.

It's not only valuable for each of us personally; it's also important for anyone who wants to help the culture evolve towards a bright future. People who are Optimal Zone resilient are better collaborators, more creative trailblazers and better able to smoothly navigate turbulent times. The world needs more such people.

This post explores what Optimal Zone resilience is, how you can develop it and how you can get its benefits. Think of it as a map for the Optimal Zone resilience territory. I'll be building on my earlier post, Your Optimal Zone, and in the process expanding our understanding of human operating system literacy, which is one of the Foundational Keys.

This map is a synthesis of material drawn from neuroscience and related sciences, the world of therapy, my own personal experience and the experience of others I know. Much of this background is new in the past few decades so it’s not surprising that this skillset is still little known or practiced in modernist culture.

Here's what I'll cover:

How our autonomic nervous system detects and responds to threats

The Neurological Reset, a practice for partnering with your ANS

Recommendations for incorporating Optimal Zone resilience into your life

Threat detection and threat response

Optimal Zone resilience is about recovering in a healthy way after being triggered into a defensive reaction, so we need to start by understanding how we get triggered and what happens when we do.

The context for this is the autonomic nervous system. As I described in Your Optimal Zone, the ANS’s overall role is to regulate bodily functions like breathing, heart rate and digestion, without needing to depend on the conscious mind. The ANS is also responsible for threat detection and response.

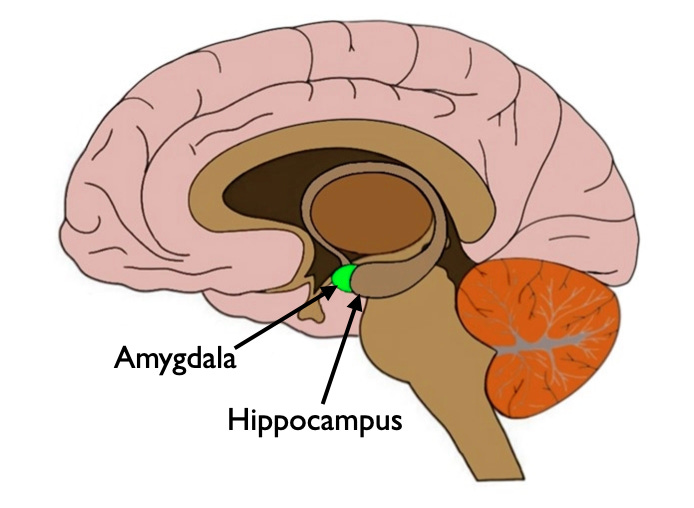

Its threat detection system has evolved over hundreds of millions of years to deal with immediate physical threats. It's about physical survival for the organism. The ANS prioritizes speed over nuance. It begins with very fast, subconscious, sensory perception (called neuroception) that's primarily interpreted by the amygdala and the hippocampus, evolutionarily-old parts of the brain.

These parts of the brain are constantly using both instinctual and learned survival-oriented protective patterns to decide if your situation is safe or if there is a threat. All of this processing happens in a fraction of a second and outside your conscious awareness or control.

If a car swerves in front of you, you will react before you're even conscious of what's happening. It’s a normal and healthy survival response to an immediate physical threat – you wouldn't want it any other way. There is clear survival value to this speed, even if your reaction might be more skillful if you took more time.

We humans, however, make things more complicated. Starting in childhood, we develop various psychological defenses that the ANS uses as it scans for threats. However, many of these trigger us in situations that are neither immediate nor physical.

For example, we can get triggered by something someone says that we find emotionally distressing. Or we feel angry for no apparent reason at someone who reminds us of a challenging person in our past. We can also trigger ourselves by imagining something unpleasant in the future or remembering something upsetting from our past.

The ANS didn't evolve for these situations and our ANS reactions are frequently counterproductive in them. Optimal Zone resilience can enable us to respond more usefully to what’s actually happening in the present.

Pathways through the ANS

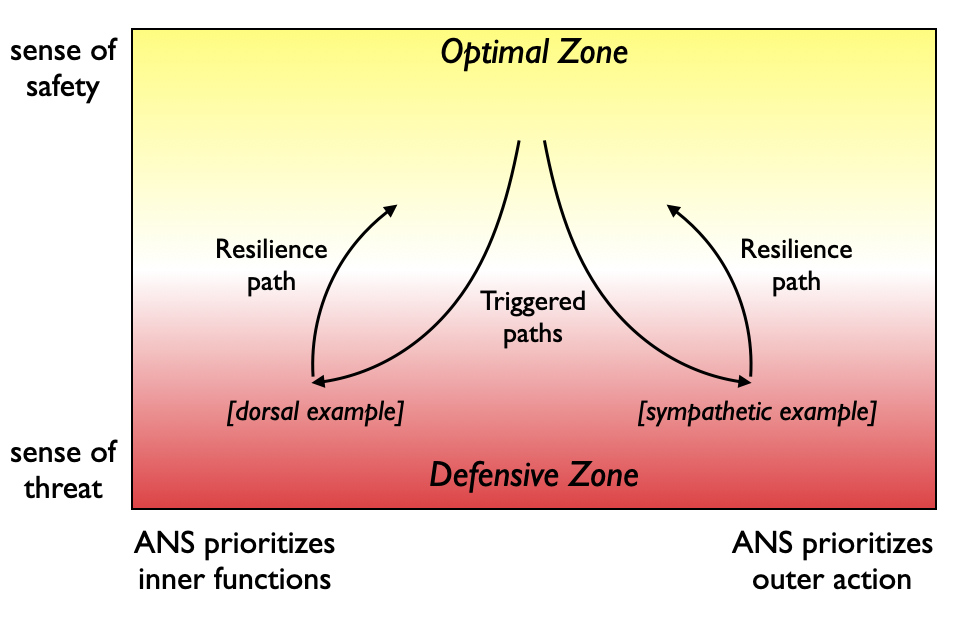

The following diagram (built on the diagram I introduced in Your Optimal Zone) illustrates how we travel through different ANS states when we get triggered and then as we get untriggered:

This shows two examples – one triggered into a dorsal vagal state and the other into a sympathetic state. It's just meant to be schematic. You can start pretty much anywhere in the diagram. The main thing is that when you get triggered, you go down in the diagram, away from a sense of safety and towards a greater sense of threat.

Your resilience is then the skillset that you can use to move back upward in a healthy way. That upward movement may be from the Defensive Zone into the Optimal Zone or you may simply move to a less intense part of the Defensive Zone. The possibilities are endless and the pathways may be more complex than what's illustrated here.

In this post, I'll mostly be dealing with the familiar case where something surprises us and we jump downward into a sympathetic activation. However, before diving into that case, I want to note that

It's possible to jump downward into a dorsal vagal state, for example if you get some news that you find discouraging and dispiriting.

It's possible to move more slowly downward with increased sympathetic activation, for example if you're under ongoing stress.

It's possible to move more slowly downward with, for example, increasing fatigue, into a dorsal vagal state where you feel overwhelmed and not safe.

There are differences of detail in how to be resilient in each of these cases but there are also many similarities. Even in the slow drift cases, there is generally some trigger event when you realize you aren't feeling as safe as you would like to. That said, the jump downward into sympathetic activation will provide a good illustration of the basic principles.

Reacting to a trigger

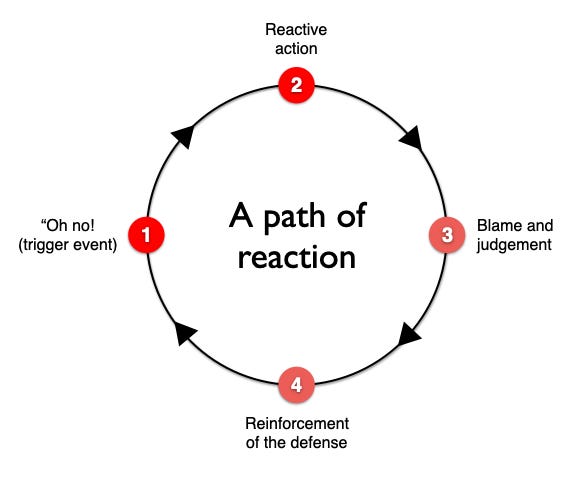

Here's a diagram for a common sequence of reactions that happen when we humans get triggered:

1 - Trigger event

The trigger event is whatever sets you off. It may be a big shock ‘out of the blue’ or it may be a seemingly small thing that pushes you over the edge when you are already stressed. Whatever it is, it sets off a cascade of activity in your body.

If you're triggered into sympathetic activation, your heart rate and breathing increase, blood flow shifts from the internal organs to muscles and brain, and adrenaline, cortisol and nor-adrenaline are released into the blood. Your attention focuses and narrows and your reaction time speeds up. Your perception becomes fast but error prone and your thinking becomes more categorical and rigid. You feel an urgency to act. You may feel angry, irritated and/or annoyed.

If you're triggered into a dorsal vagal state, your heart rate and breathing decrease and blood pressure and body temperature drop. Blood flow shifts to the internal organs from muscles and brain, and acetylcholine, endorphins and vasopressin are released into the blood. Focus and alertness decrease, your thinking slows, decision-making becomes harder and your memory is impaired. Taking action becomes harder. You may feel hopeless, helpless and/or numb.

The shift in the body can be dramatic but it can also be subtle. Intense triggerings leave strong impressions but are less common. Based on my own experience and what I gather from others, many people get mild triggerings multiple times a day. We may hardly notice them but they still play an important role in our lives. I'll have more to say about mild triggerings in the Practice section later in this post.

2 - Reactive action

How do we react when we get triggered? It depends on many things, including how intense the triggering is, whether you're triggered into a sympathetic or dorsal vagal state, your personal history and psychological defenses, and our cultural inheritance going back thousands of years.

The circle image above is intended to illustrate a moderate triggering (strong enough so you notice but not overwhelming) into a sympathetic state.

In this case, the default reaction is to immediately focus outward on the ‘cause’ of the triggering and feel a great urgency to ‘do something’ to reduce the threat from that ‘cause.’ For example, did someone say something that upset you? You fire back, in your mind if not out loud.

Or you may have learned that it's not safe to be angry or that you need to be ‘tough’ and ‘strong’ so you use your will to try to suppress your urge to act and other aspects of sympathetic activation. This may change how things look on the surface but your ANS still reacts.

3 - Blame and judgement

Then your mind starts to build a narrative about what's going on. If you don't have Optimal Zone resilience skills, you're likely to follow patterns you've learned from your family and/or from the broader culture. Most cultures in the past 5,000 years have had a strongly moralistic, will-based sense of why things go wrong, consistent with their overall categorical, power-struggle approach to life. There was no sense of multiple influences, only single causes – therefore the blame needed to be pinned on someone. This perspective carried right through the Age of Enlightenment into our modern society, where it is enshrined in our legal system.

So it’s easy for us to respond, when we get triggered into a sympathetic state, by looking for someone to direct blame and anger towards. That ‘someone’ can be another person (or group) or, in some situations, we can turn inward to blame ourselves.

The blame response – outward or inward – is profoundly disempowering. You see yourself as a victim of either the other person’s actions or your own out-of-control behaviors. You make your state-of-being dependent on actions beyond your control and thus diminish your own agency.

4 - Reinforcing the defense

As the immediate crisis of the trigger event subsides, our tendency is to push the whole thing away, feeling ‘glad that’s over.’ But, of course, it isn’t. The defensive pattern that got triggered in the first place is still there and your threat detection system has had its belief – “I’d better be on the lookout for this pattern” – strengthened, deepening the memory-groove for the next time it comes up.

The line connects from this Step 4 back again to Step 1, the trigger event, to indicate that it's likely that some time in the future you’ll encounter a similar situation that will trigger this now-strengthened defensive pattern. This cycle has set you up for the next one.

Your turn

This is just one example of the steps we humans often go through when we react to some trigger. What do you typically do and what have you seen others do? If you’d like to explore, I invite you to draw a circle, put as many steps around it as you like with labels that tell the story of the reaction patterns you’re familiar with.

A better way to respond

Fortunately, there are other ways to respond to a trigger. What follows is an approach I developed and use, drawing on and synthesizing the work of many others. Feel free to adapt it and know that there are potentially many useful variations.

The basic strategy of the approach I’m offering here is to redirect the urge to act from an external to an internal focus so you can shift back toward your Optimal Zone before you attempt to deal with the external situation. This enables you to deal much more skillfully with the perceived threat. This approach works well when the perceived threat is neither immediate nor physical and can even work when it is.

This approach also supports a longer-term strategy for easing or even resolving some of your psychological defenses.

Many of our defenses get their start in childhood, even in our infancy. Something distressing happened to us and we weren't able to find our way back to safety in a healthy way. Instead, our subconscious tried to wall off the memory and created a defense against re-experiencing or even remembering what happened.

We did the best we could with the knowledge and skills we had at the time, but these early defense patterns are often simplistic and full of misunderstandings. Nevertheless, they got frozen in time. They may have gotten layered over with more recent experiences but the underlying beliefs and response patterns still provide the foundation of our reaction.

To update, ease or even resolve these defense patterns, they need to be brought to consciousness in order to modify them. When this kind of defense is triggered, it reveals itself and, if we are prepared, we can gain valuable insights about it while it’s active. The following approach can help us do that.

Steps on the path

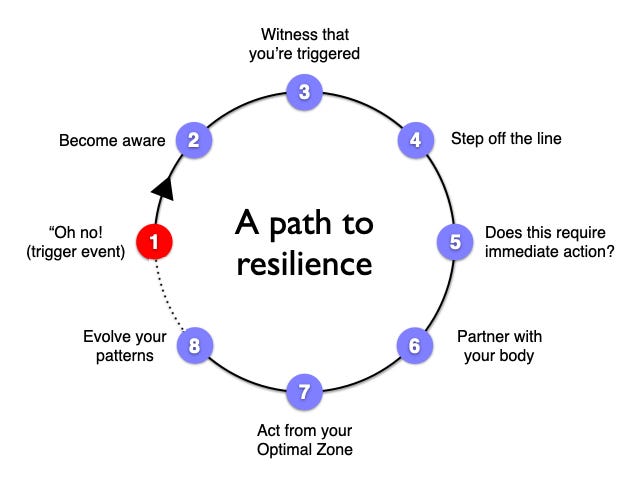

Here’s a diagram that represents the steps in this approach to Optimal Zone resilience:

1 - The trigger event

The starting point for this circle is exactly the same as in the circle above.

2 - Become aware

The first step out of being engulfed in the reactive triggered state is to notice that you're triggered. It's a crucial step to shift at least some of your attention toward what's happening inside of you, instead of focusing purely on the ‘cause’ outside of you. This is essential for regaining some agency.

It takes practice to recognize the signs that you're triggered and recover some inner awareness. If you feel annoyed, anxious, angry, vigilant, irritated, fearful, depressed or anything similar, you're in your Defensive Zone and you've likely been triggered.

It sounds simple but when you're in the midst of a triggered state you may be flooded by its defensive energy as well as possibly feeling totally self-righteous. Recognizing that you're triggered may be the last thing your triggered mind wants to do or is even able to do.

However, with practice, you can come to see that recognizing that you're triggered doesn't invalidate your point of view. Rather, it helps you deal with the situation more skillfully with better results.

3 - Witness that you're triggered

This step is optional but I’m including it because I’ve found that, when the situation allows me to do it, it’s proven valuable for moving more fully back towards my Optimal Zone and for easing and resolving my defense patterns.

The previous step is about simply becoming aware that you have been triggered. This Step 3 is about witnessing what you’re experiencing.

The length of time you spend in this witnessing step can vary enormously, from seconds to minutes, depending on the situation and how much you want to learn. If you’ve been triggered in a live situation, like a conversation or a meeting, you may need to move through this step quickly.

With whatever time and depth the situation allows, this step is about turning toward the defensive pattern while you’re still immersed in its energy, being with it in a non-judgmental way and allowing yourself to observe the feelings, beliefs, needs and fears that are its components. Approach it with curiosity and self-compassion, not control and suppression. It’s part of you, it came into being to protect you and it’s doing the best that it knows how even if it’s woefully out-of-date for who you are now.

Witnessing in this way allows you to accept it as part of you but also realize that it isn’t all of you. You may discover things about this defense pattern that will help you become aware of it sooner the next time around. You may also be able to recall the experience later in a calmer state to work on healing and easing it.

This is also a good time to mentally locate your current ANS state on the Optimal Zone/Defensive Zone diagram. How strongly are you triggered (how far down the diagram)? Are you in a more sympathetic (urgency to act) or dorsal vagal (dispirited and de-energized) state? Doing this connects you to a bigger picture and supports your shift into more of a witness perspective.

4 - Step off the line

Next it's time to disengage more from the energy of the triggered state. In the martial art of Aikido, the first thing you're supposed to do when you realize you are being attacked is to move ‘off the line’ between you and the attacker by stepping to the side, perpendicular to the direction of the attacker's momentum. This is intended to give you a chance to center yourself and assess the situation.

It's a beautiful physical expression of changing the dynamics of the situation by doing something that is neither fight (i.e moving toward the threat) or flight (i.e. moving away).

As a metaphor, there are many ways to ‘step off the line’ as long as you break out of the fixation on whatever you feel is triggering you and allow yourself to start moving back to your Optimal Zone. It can be as simple as a conscious slow breath or even a mental reminder of a supportive bigger picture. If you're triggered in the midst of a conversation, you might find some way to take a break like "Let me think about that" or "I'd like to sleep on that."

With practice, awareness, witnessing and stepping off the line can happen in quick succession, indeed within a fraction of second if the situation requires it. Aikido practitioners learn to do that and we can too.

5 - Immediate action?

If this is a real physical emergency, like a car swerving in front of you, your body will swing into action well before you're even aware of what is happening. Yet most of our triggerings aren't like that. We have at least a few seconds to become aware, step off the line and, from that perspective, assess: does the situation require some kind of immediate action? For example, is someone injured? If so, of course you need to deal with it.

However, much of the time things aren't as urgent as we think they are. If you've been triggered into a sympathetic state, you will feel a strong urge to act – to reply to that person, to that email, to that social media post right now! Better to redirect that urge to action into turning your attention inward, to observing, understanding, stepping off the line, slowing down and responding to the triggering process as it is unfolding within you.

6 - Partner with your body

The trigger event has set off a cascade of changes in your body, your mind and your emotions. Since the body sets the context, unwinding these changes is easiest if we start with it.

We can help our bodies feel safer by stimulating the ventral vagus nerve. The easiest way to do this is with breathing and releasing tension in muscles. There are many practices you could use. Later in this post I'll describe a practice called the Neurological Reset that I developed and we used in the original Bright Future Now course. But if you have other easy practices you know and like that stimulate the ventral vagus system, feel free to use them. In any case, it's good to have a toolkit of simple practices that you've learned thoroughly enough so that you can do them when you need them – that is, when you're triggered!

Fully shifting out of a triggered ANS state often requires some time. While I can feel real benefit in the first minute with the Neurological Reset, it may take many minutes for my body to really settle depending on how strongly I've been triggered. My mind and emotions can take even longer.

I find that starting with the breath and the body is one of the best ways to reorient the nervous system to safety. My mind and emotions may benefit from additional reassurance and reframes, but these are more likely to be effective when my body feels safe.

7 - Act from you Optimal Zone

By this point you're sufficiently back toward your Optimal Zone to have the perspective and capacities that can guide your discernment of what, if any, further actions are appropriate to bring healing and resolution into the situation. Now you can turn your attention outward and address the initial external ‘cause’ in a more skillful and effective way.

8 - Evolve your patterns

If you choose to work more intentionally towards resolving your defensive patterns, the experience from this journey into and back out of the Defensive Zone can provide useful insights. I plan to have more to say in a future post about how this work can be done. For now I'll just suggest you consider incorporating this practice into whatever you may already be doing, whether on your own or with a skilled practitioner.

In any case, going through these steps will likely reduce the charge around this particular defense. If or when you do encounter a similar situation in the future, this cycle has given you a positive experience for how you can respond, and that gives your brain fresher memories to draw on. This easing of the defense pattern is indicated by the dotted line from Step 8 back again to Step 1, The trigger event.

With practice over time, at some future trigger event, you may even begin to feel, "Oh good, now I can learn more about what triggers me" instead of "Oh no!"

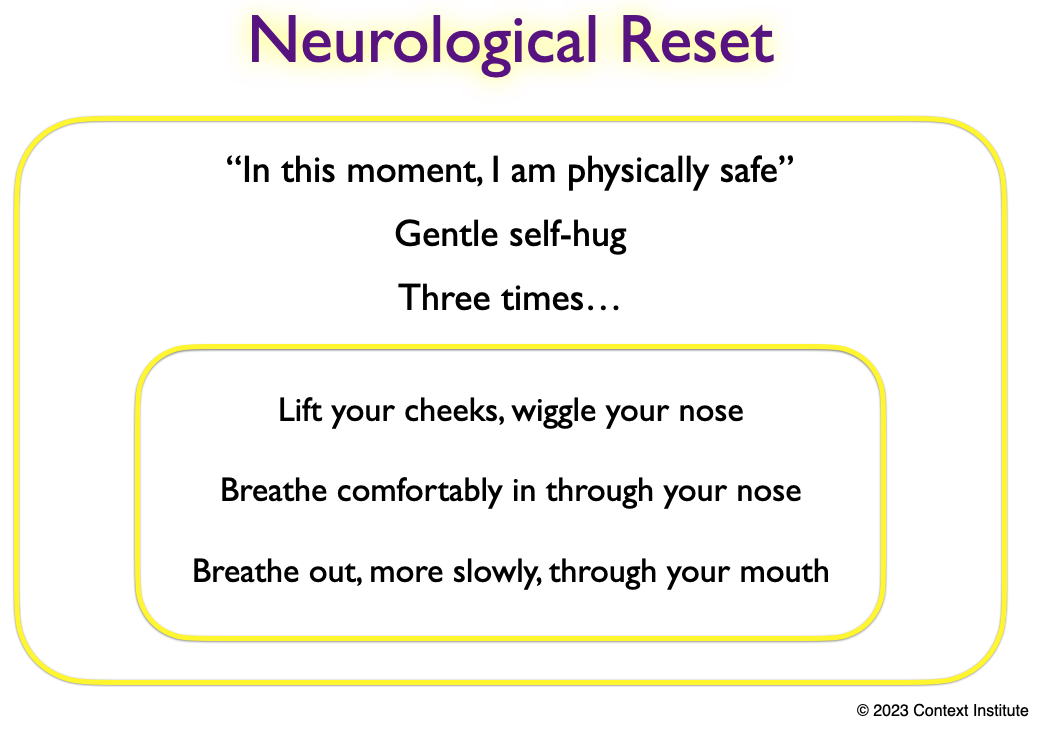

Neurological Reset

This is the practice I mentioned in step 6 above. It stimulates the ventral vagus system and thus helps to move you back toward your Optimal Zone. In the following 7-minute video, I explain the principles behind it and demonstrate it.

If you'd like to add it to your toolkit, I recommend that you practice it at least three times a day for a number of days during a week to build up the habit. Do it both when you're triggered (even mildly so) and when you aren't. It's really quite simple, as you'll discover once you've run through it a few times. The goal is to get so familiar with it so that

Even doing just the breathing (e.g. if you’re in a public setting) will evoke your memory of the full practice and be quite helpful

You can use it without needing to think about how to do it.

Then it can help you when you really need it!

Here's the image that summarizes it. If you’d like to have it easily available, feel free to download it and put it on your phone or print it out.

Putting it into practice

If you’d like to work on becoming more Optimal Zone resilient, I recommend the following:

Practice the Neurological Reset (or something similar) until you know it by heart.

Print out A path to resilience and put it somewhere so that you will see it often.

Identify a recent time when you were mildly or moderately triggered that you’d like to use for practice purposes. Start with the Neurological Reset to resource yourself and then imagine going through the steps in A path to resilience for that situation. Do a similar imaginative practice with other times you were mildly or moderately triggered.

Increase your awareness of when you're mildly triggered. Don't push these mild triggerings and their feelings aside but welcome them as a practice ground.

If you like, develop your own version of A path to resilience.

If you can find someone to go on this learning journey with you, you can provide each other with mutual support, encouragement and useful feedback. If it's someone you live with or work with, even better.

The Bigger Context

The focus in this post has been at the personal level. That's certainly where we need to begin but I don't want to leave it there. As valuable as Optimal Zone resilience can be for each of us individually, it can be even more valuable when it is part of the explicit shared culture of a group. The group could be as small as two. It could be the size of a team or as big as a large organization. Eventually, it could be humanity as a whole.

When it's the norm within a group, everyone is able to be more at ease, more transparent, more honest, more compassionate and more creative knowing there is a good, respectful way to deal with the inevitable interpersonal triggerings that are likely to occur. Such a group can devote more of its energy and attention to things that really matter, to be both joyful and productive.

In addition, while it can stand on its own, Optimal Zone resilience doesn't need to. It's only one aspect of being savvy about psychodynamics. It pairs happily with being skillful with diverse modes of cognition. And it powerfully supports win-win-win collaboration. The more we develop additional skills in those Essential Capabilities, the better it gets.

I invite you to think of Optimal Zone resilience as a doorway into a rich, vibrant territory that can lead you, and those you share it with, to a greater lived sense of harmony within, with others and with nature. It's a doorway into a bright future that you can walk through now.

Let me know if you have any questions.

Thanks!

I’ve borrowed the “8 c’s” from Richard Schwartz who uses them to describe what he calls the “Self” in Internal Family Systems. There are differences between the IFS Self and who you are when you’re in your Optimal Zone but the 8 c’s provide a lovely point of convergence.